It’s hard to gauge how good or successful a film soundtrack is when you haven’t actually seen the film. On the one hand, the soundtrack might just be full of cracking songs or the most divine instrumental work that requires no images to be put to it, making it a winner on its own musical merits. On the other hand, what may appear lifeless and pointless might suddenly make so much more sense and have a greater sense of worth driven through it when your mind can associate it with the correct scene. But if music really requires an image too, does it not go beyond being just music? Take a soundtrack like the one to the hit-indie film Juno; the majority of individual songs on the soundtrack stood up on their own and pleased everyone who enjoyed the quirky nature of the film and its main character. But part of the enjoyment (for me at least) came from hearing the song and then remembering the scene when it was played in the film. The film helped give a new lease of life to the songs and/or another referential set of images for them.

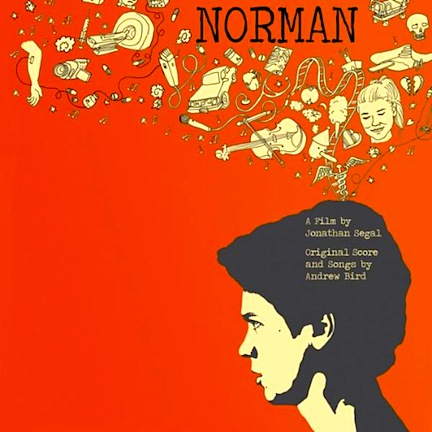

But not all films are Juno and aren’t likely to gain the same kind of cult status both the film and the soundtrack have. Enter Norman, and it’s Andrew Bird soundtrack, a limited release film about a young and troubled individual falling in love during life’s hard-hitting turmoil, as underrated indie violin hero Andrew Bird creates music to accompany him.

There’s no point in being dishonest; I’ve not seen the film (mainly due to its being on limited release on another continent) but many music fans (myself included) seem to putting their attention to the soundtrack due to the fact that’s been written by Bird. As a musician, Bird’s no stranger to instrumentals (his last album, Useless Creatures, was filled with them), but his work on this soundtrack is more intriguing than usual as it has me wondering how the creation came about.

At times I can imagine Bird standing in a room creating music spontaneously as he watches the film, such as the high shrieks on “Nice Hat / Exit Sign / Angelo Speaks” or the rambling guitar melody on “The Bridge,” which gradually builds itself up with numerous violin streaks. Elsewhere the music often takes sudden turns or dramatic shifts, altering the tones with only a few seconds notice. It’s on track like “Scotch and Milk” or “Afterspeak / Things Come to a Head” that match this description, that it feels easier to imagine Bird working to a director’s notes on how the mood of the piece should be and what the music should help accentuate (if anything).

And, as I said, it’s intriguing to hear Bird work in this domain but it does often feel like the best of his work is being compressed and condensed. Obviously one has to take into account that this is a film soundtrack first and a collection of original compositions second, but there are times when listening to the music Bird has created and feeling as though it could be something a whole lot more. One of the strengths of Useless Creatures and of Bird’s fantastic live shows is that he opens up his songs, allowing each sound and layer to breathe and come together at its own pace. Here, on the soundtrack, it rarely taps into the wonderful quality.

Still, it’s not at all unpleasant – Bird fans will still find plenty of interest here. Fans of his instrumental work will enjoy the best of it: the slow groans and yawns of “Hospital” and the almost regal sweeps of “3:36.” Those who are fonder of his lyrical wordplay won’t be too disappointed by the pair of original tracks that, perhaps for the first time in Bird’s history, have the theme of love as a centre point. “Arc and Coulombs” has all the elements of a light acoustic Bird track (breezy whistling, glockenspiel, acoustic strums) that goes from a nautical references to “Go ahead boy / do some something dumb / there’s no shame,” all in the space of two minutes. “Night Sky,” another acoustic ballad, is a tad more interesting as it ponders “What if we hadn’t been born at the same time? / What if you were seventy-five and I was nine?” It’s interesting to see Bird tread into territory full of plenty of potential sentimentality and still remain clever and insightful throughout, showing his worth is well beyond complex wordplay and that he’s capable of creating more human and touching moments. There’s also a few examples to show Bird can work in the absence of a pleasant melody, experimenting (to some success) with screeching distortion (“Build Up to the Fall”) and darker tones (“Cancerboy Strikes Again / Monsterstream”).

The three other tracks on the soundtrack that don’t have Bird’s name beside them also help proceedings along and shoot some life into the surrounding instrumentals. “Rabid Bits of Time” by Chad Vangaalen isn’t actually too far off a Bird track itself, mainly due to Vangaalen’s voice which, though a bit higher and more ready to crack than Bird’s, has a definite similarity. The redux of Wolf Parade’s “You Are A Runner And I Am My Father’s Son” (quite likely another point of interest for passing music fans) turns out to sound more like one of Spencer Krug’s Moonface tracks combined with the dying embers of one of Wolf Parade’s last practice sessions than something by the full band. To an outsider these two tracks though do seem to hit the subject matter of the film on the head and while their presence is most welcome (especially the latter), they remove any sort of subtly the instrumental tracks around them might create.

But I can’t make an entirely valid judgement, since I haven’t seen the film. It’s easy to picture the sort of thing that might be happening when the music is playing but the strength of Bird’s compositions is that they never really give anything specific away (not even when he’s singing). While I can’t foresee Norman becoming the next Juno (at least not until it gets a much wider release) in terms of cult status, the soundtrack can at least be added to Bird’s back catalogue, hopefully as he takes another step somewhere more melodic and memorable than his work for the big screen.