Julian Koster always seems to be unfairly pegged as one of the lesser Elephant 6 musicians. This seems to be due in part to a relative inauspiciousness when it comes to his public persona – though he’s never shied away from completely fantastical elements like overly elaborate set designs and tour methods – and his habit of playing the expert studio musician on many E6-related releases. The albums he has released as The Music Tapes have always been artistically inventive, though sometimes creatively scattershot. His natural inclination towards oddly arranged, though instantly memorable, melodies have repeatedly made him stand out among the psych-pop impressionism of fellow E6 bands like The Apples In Stereo, Elf Power, and Circulatory System.

His debut album, The 1st Imaginary Symphony for Nomad, was an odd conglomeration of spoken word lo-fi experiments and curiously arranged pop songs. His sophomore album, Music Tapes for Clouds & Tornados, was a more cohesive collection of crooked psych-flavored pop songs that he set down on old-fashioned recording machines. Despite the antiquated recording methods, his sophomore album felt more focused and consistent in terms of how he approached the material than on his debut, and the songs — and Koster himself — gained a greater sense of maturity and technical proficiency as a result.

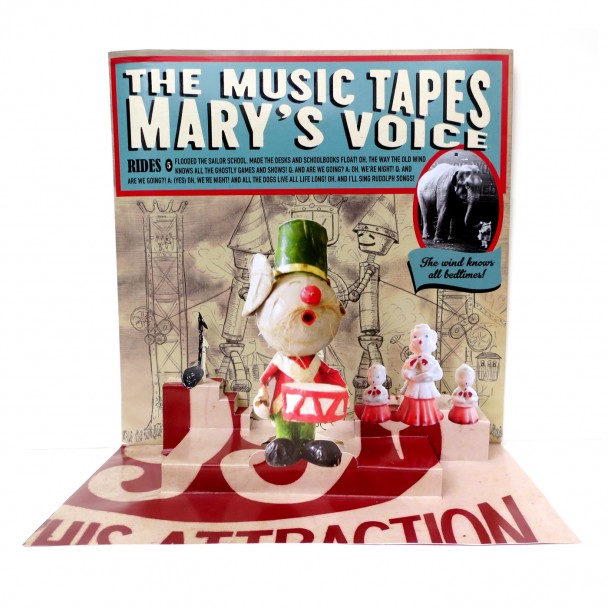

Mary’s Voice takes the whimsical imagery and lo-fi dynamics of his debut, fashions a more palatable version of them, and proceeds to create a set of songs that uses the more focused musical stylings of Clouds & Tornados as a model. The result is an album that is inextricably tied to Koster’s past but one that is also well aware that creative development was sorely needed. The determined sense of purpose and attention to detail scattered across this album seem light-years ahead of his past work. And yes, thankfully, his trademark musical saw is always right by his side.

From the opening nostalgic familiarity of “The Dark Is Singing Songs (Sleepy Time Down South)”, Koster and crew set out to pay homage to their earlier works while also setting a higher stand for themselves in terms of songwriting and creative unity. This track sounds like it was recorded on an old victrola and then run through some kind of carnival filter, but the slightly morose and world-weary melody that weaves through the fidelic hiss and tattered horns is a wonder, seeming to take on characteristics of all the instruments being played and becoming somewhat of a compendium of the song’s many influences.

Despite the album’s grounding in modern lo-fi indie theatrics, these songs feel old, as though each instrument and strained note has a long-standing history. Koster wants us to remember a time when electronics and music served the singer and not the other way around. The railroad crossing bells that ring at the end of “Go Home Again,” with its cascading waves of droning harmonium, sound as though they’re calling unnamed passengers home. But whether home is a place in this context or a particular point in history is up for debate. It’s the album’s innate sense of musical preservation and discovery and its need to celebrate, or possibly just to recognize, a romanticized version of history that sets this album leagues above his previous releases.

Even some of the shorter interstitial tracks, like the back-to-back sequence of “Saw and Calliope Organ on Wire” and “S’ Alive (Pt. 1),” don’t diminish the flow of the album. These tracks take that antiquated feeling from the opening track and further develop the idea that Koster feels honor bound to memorialize some vague, hazy version of Dustbowl-history in his own inimitable way. The album could have benefited without his inclusion of “Intermission (Pt. 1)” and “Intermission (Pt. 2),” however; they run a total of fifteen seconds and amount to what is roughly a dead spot in the middle of the album. Why he feels a particular need to do this is anyone’s guess but it’s not without precedent, as there are similar moments on his previous albums.

The record does gain a great deal of weight from its two centerpieces, the ever-changing, Christmas bell and banjo-adorned “To All Who Say Goodnight,” and “Playing Evening,” with its cacophonous rush of crashing cymbals and Koster’s own tinny howl. These two songs stand out as some of the best Koster has ever written and recorded.

Mary’s Voice allows Koster the opportunity to finally work his way out of the shadow of his previous associations — Olivia Tremor Control, Neutral Milk Hotel, The Apples In Stereo — and show that he was never just another supporting player. His contributions in those seminal bands only hinted at the burgeoning musical drive that would come to fruition on this record. If his debut was the album on which he shed his youthful tendencies and Clouds & Tornados found him developing his own independent outlook, then Mary’s Voice is his up-to-now defining musical statement. With songs that unspool in unexpected ways and feel centuries old in spirit, he has finally given us something that matches in execution what he’s been repeatedly trying to show us through his boundless imagination for the past decade: that the worlds of art, music, and experience are all linked in sometimes subtle but wholly tangible ways. With this release being the first half of a planned two-part album, he has space enough to further expand on this already compelling perspective. It may have taken him a few tries but through Mary’s Voice, Koster has finally found his own.