How does one “review” a product forty-five years past its prime? Even in this thought, you’ve already lost: to suggest a set of recordings such as The SMiLE Sessions hinge on the trappings of a time period is to take away from their endurance. Again, you’re trapped. How can you illustrate the endurance of a recording never technically released? Easily. Most albums that stock your local Best Buy will spend years on those shelves, before moving to the bargain bin, if they’re lucky. The music industry is fickle, and consumers, fickler still. You can’t inspire people to remember records that once ruled the market, they fade from the industry’s collective memory completely, just ask Roy Orbinson. SMiLE was recorded from May to May, 1966 to 67. It was never released, not a copy sold. By all rights, that’s as dead in the water as a dropped rapper’s album: it’s nothing, no one is going to ever hear it, and no one is ever going to ask about it. SMiLE has been bootlegged song by measly song, re-recorded by its original visionary in an entire expansive re-imagining not ten years ago, and still, the ultimate release of these original recordings is an event to end events.

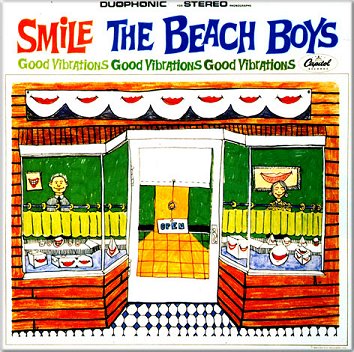

All this is obvious to a longtime lover of music, but some younger fans are sure to question: just what’s the big deal, in 2011? It’s 1966, The Beach Boys are high on the release of the greatest artistic accomplishment of their career, the differences that would drive them apart were already festering, and above all, now they had to do it. They had to top Pet Sounds. Brian Wilson wanted to record the perfect “teenage symphony,” and had started off without fail with “Good Vibrations.” Wilson had never been one to go about creation with ease, and with The Beach Boys’ first million-seller, he created a brilliant obsession that would grow into the monster that strangled his ‘perfect symphony.’ He had begun doing something then entirely unorthodox: recording each section of music – essentially, each sound – with an independent, long running session, all later pieced together, to create the nebulous concept of a flawless single that surely only existed in Wilson’s head. It all sounded crazy (and expensive), but it worked. The powers-that-be surely raised eyebrows at the price tag, but would endure anything for an entire album’s worth of “Good Vibrations.” Wilson even found the ideal writing partner in Van Dyke Parks. So, where did it all go wrong?

The popular, cool answer is Mike Love. He had been a voice of uncertainty during the increasing artistry of the Pet Sounds sessions, and had only grown more agitated at blowing budgets on Tannerins and the like, when those involved in the sessions recall them, they’re quick to point blame: Mike hated the album. He’s an easy target, and not at all an unfair one. However, considering The Beach Boys’ own prominence in the very culture that supports such a lifestyle, it’s important to note: Wilson had gone a tad off the deep end. Mary Jane had long been a friend, but Wilson had grown increasingly close with Lucy (we mean acid, folks). This both allowed for the extreme insights he had during recording and began to dissemble the already overworked and paranoid Wilson. He became convinced the “Fire” section of ‘Elements Suite’ was responsible for local fires, ceasing recording of the material, had his band dress in firemen hats, and so on. Parks avoided even entering the studio.

Yet, it reached beyond even this. Most musicians described Wilson as respectable during their sessions, saving his transgressions for outside the studio. It was resistance that broke Brian Wilson, the same resistance that turned what may have been his proudest moment, “Heroes and Villains,” into an afterthought. His own band member despised the album, but it was ultimately the music’s own brilliance that unraveled it. This is the strange tragedy of SMiLE, had it been released when it was intended, it may well have changed music forever. Yet, it just may as well have been overlooked, a recording destined for recognition long past its creation. So, perhaps, this painfully gradual release has only ensured its legacy, unleashing it on a generation of listeners trained to understand it. Despite all the bootlegs, the newer version, and all the material released on other albums across the years, the resurrected SMiLE still commands force. Somehow, allowing it its true moment on the shelves has solidified the record’s historical importance. In 1966, Brian Wilson and friends recorded an album that could have changed the world. The truth is, Wilson had thought the record would be a classic, every bit as worthy as many now consider it. Alas, the droves had wanted more surf music. While British musicians were warmly embraced for their new, burgeoning ideas, America suffocated one of its idols with their expectations, a complacent, dull desire for the one thing our country has never seemed to object to: more of the same. So, perhaps SMiLE did change the world, perhaps we can learn from it, and not make the next poor genius in line with an idea suffer for it.