Daniel Lopatin’s Oneohtrix Point Never and Jeff Witscher’s Rene Hell projects seem unlikely bedfellows. Though both clearly mine the similar crossover brands of ambient minded music, the frenetic microsampling of Lopatin’s landmark OPN release, Replica, and Witscher’s analog synth explorations butt heads on levels beyond even simple textures. Where Lopatin deals in the weird, the wondrous, and sometimes the wacky, Witscher instead zeroes in on a more straight-faced, tight-lipped approach. You’ll find no samples from classic television commercials on The Terminal Symphony, and the sort of spacey journey that Rene Hell consistently takes has been absent from OPN’s work since Returnal. Yet here they sit. Despite their differences, Witscher and Lopatin have penned tracks to sit on opposite sides of the same wax. While their physical closeness still doesn’t reconcile their sonic differences, they each present compositions representing interesting shifts for each of their respective projects.

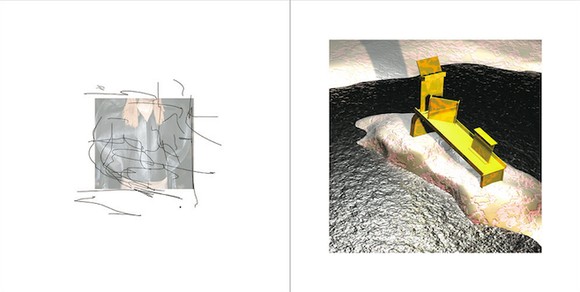

Lopatin’s contribution sits firmly on the A-Side, more ambitious in scope and more confrontational in its composition. Music For Reliquary House consists of a 22-minute piece culled from his collaboration with visual artist Nate Boyce. At its most basic level, it’s a much stranger beast than even Replica–where Lopatin previously delved furthest into the absurd. Here he focuses more heavily than ever on little vocal fragments, crafting interstellar popcorn out of samples chopped far beyond recognition. Though his fascination with the human voice is nothing new, he aims here less for an ethereal sweep or space-filling meander, opting instead for pointed, harsh, and chilling textures–far more unsettling than the realms explored on Replica.

If nothing else, Music For Reliquary House most clearly replicates OPN’s method of live performance, taking these subtle sweeping textures and turning them into something much more slippery. Tracks fade into one another, recognizable samples are rendered incomprehensible by swaths of noise and the experience is a whole lot less inviting than his studio efforts might suggest. With Music For Reliquary House he wholeheartedly embraces this philosophy, at least in the short form, punctuating these vocal sampling experiments (think “Nassau”), with noisiness straight out of your favorite copy machine. It’s all a bit overstimulating at points, but just when it all becomes too much, Lopatin brings back the soothing tones. Though they may still be marked with the same sort of analog noise, these more laid back segments punctuate the harshness in a fashion that makes the whole listen worth the effort.

While Lopatin’s side of the LP functions cohesively within the context of the OPN pantheon (despite its harsher construction), Witscher’s is a bit more of an oddity in context with the rest of his career, though this new shift is no more suited for accompanying Lopatin’s work. Here, Witscher delves into a suite of more classically composed songs–largely ditching his spacey synth journeys in favor of the simple melodies of tightly arranged acoustic instrumentation. The stately hushed piano arpeggios are pure Gymnospedi-an Satie coated in swaths of glitchy electronic noise. And that’s the pattern that Witscher explores on In 1980 I Was A Blue Square. He aims less to explore the cosmos than to compose something simple and then turn it into something stirring. Though the noise washes are nothing new for Rene Hell tunes, they’ve never been paired with such simplistic accompaniment. “Untitled Solo 4” takes simple swelling string flourishes and garnishes them with pointillist blips.

It’s straightforward for sure, but Witscher has hit on a winning combination, pairing these obvious digital elements with the visceral organisms that serve as the bases of these tracks. “Qi” relies further on the float that marked previous Rene Hell pieces, but it’s grounded by this acoustic instrumentation. Where previous tracks relied on the obvious distinction between the warm tones of his new constructions and the digital coldness that he plaited them with, Witscher blurs the lines here. There are obvious elements of both compositions, as string swells unearth themselves from the mire, but by and large, the haze is unidentifiable–uniform in its unique sweep, but with its components guarded. The fog is distinct, but its origins indeterminate.

It works well then, that the beauty of Witscher’s contributions function to offset the challenge of Lopatin’s latest work. For as a package it’s rise and fall, tension and release, harshness and unrelenting beauty. Without the organic warmth of Witscher’s side, Lopatin’s vocal manipulations might have come across as too unwieldy, too formless, too haughty to be revisited with any sort of regularity. The beautiful chiaroscuro of Witscher’s works function to assuage any of the discomfort Lopatin might have brought about. Lopatin and Witscher on two sides of vinyl really never would have worked in any sort of musically homogenous relationship, but as two dichotomous pieces they work better than anyone might have ever imagined.