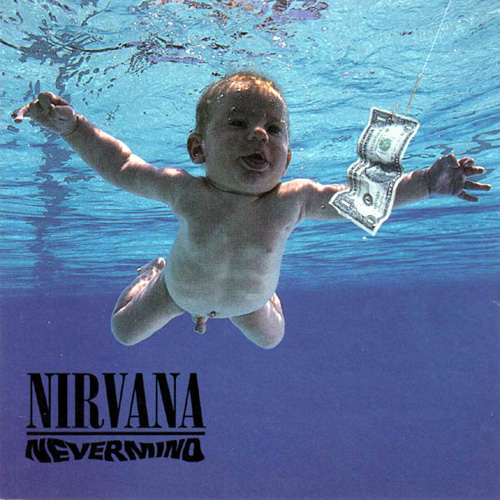

Looking back now, it’s hard to fully grasp the impact of Nirvana’s Nevermind. Big bands had come and gone over the years since the Beatles, but few had sparked such a cultural zeitgeist, nor connected as directly with the heart of their generation.

Of course, much has been written of Kurt Cobain over the years since his suicide, and an understandable emphasis has been placed on how disenfranchised he was by the band’s success – that he had always idolized underground punk bands and their commitment to anonymity – but this was hardly the first time an artist had disowned his largest success. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was surely tiresome to play time and again, but just imagine being the guys who wrote “Free Bird.”

Cobain’s inner turmoil is indeed a large part of what made the music connect with a generation born of cynicism. The ‘80s had provided a nonstop party and the music had been its soundtrack, but by the end of the decade it had all come crashing down; that’s why the grunge revolution hit as hard and as suddenly as it did. And though the music tended to express feelings of alienation and loneliness and suppressed rage, Cobain was the first of the grunge singers to marry that with innate pop sensibilities (whether he realized it or not). A song like “In Bloom,” in spite of its snarling riff and screaming chorus, is – suitably, given its lyrics – impossible not to sing along to, even if you don’t know what the hell he’s saying.

It’s difficult to write about an album this immense, this respected, this canonized by pop culture and even attempt to bring anything new to the table. What is there to say that hasn’t been said already, and by better writers? “It changed everything.” Well, no, not quite; but it certainly ushered in a whole new era of music, and with that came an influx of imitators, none of them able to come close to the cultural behemoth that the band had transformed into. And Cobain’s unfortunate passing in 1994 only helped solidify the group and this particular record as pop culture staples, images of both forever destined to adorn dorm rooms worldwide.

The new 20th anniversary reissue of the album comes in various forms. The standard two-disc set is the best bet for casual fans – the extra disc contains various demos and b-sides, as well as recordings from the band’s BBC sessions. It has been reported that the “Boombox Rehearsals” included here have been available in the past, released on the With the Lights Out box set. Indeed, much of this material might have been previously devoured by the band’s die-hard fans – and, unfortunately, a large portion of it is just that: material reserved for the obsessed. The most interesting bonus material may well be the Butch Vig recordings; lacking the “slick” aesthetic of Andy Wallace’s work that made its way to the final version of the album, Vig’s work is closer to the sound of the group’s first record: less polished and, as some might say, less mainstream. Nevertheless, it’s not drastically different from what you’re used to – unlike the remarkable changes between The Cult’s original Electric sessions and the final LP, Nirvana’s tracks never changed much from a songwriting standpoint; just the production values. Nothing here will blow you away, but it’s worth listening to as a curiosity if you are a fan.

What should be noted is the record’s remastering, which is both a blessing and a curse. Those listening through standard earbuds or speakers will probably enjoy the louder sound, and on that level the record definitely sounds more clean and polished than ever before and may hold some appeal; but for others, the quality is lacking: the songs have become a victim of the so-called “Loudness War,” which is ironic considering the remastering was engineered by Bob Ludwig, who, in 2009, publicly condemned the Loudness War as being one of the primary issues negatively affecting the music industry.

What happens by jacking up the volume on these songs is that you lose dynamics, which were particularly integral to Nirvana. Cobain was a fan of soft verses and loud choruses; it reflected the emotional rollercoaster of the lyrics, and you could feel the rage when Dave Grohl’s drums kicked in. The remastering on this album essentially removes those dynamics, so that the listener is left with a song of equal volume from beginning to end. When the album finishes, you feel battered and thrashed about, and not in the way the band intended. Of course, if you’re inclined to believe Lars Ulrich, most people “don’t give a shit” about this phenomenon, and if you’re one of those people, then you’re in luck. And if not, well… ready the Advil.

The ultimate consensus on the 20th anniversary re-release of Nevermind is that the album you know and love is still the album you know and love, and it goes without saying that the music contained here is both legendary and essential: one of those rare, near-flawless works of art that only grows finer with age. The bonus material is interesting, but not something a casual fan might be inclined to revisit; and while the poor job on the remastering will not perturb the average listener, die-hards and audiophiles should hold on to their original discs just in case.