Having released her debut album 15 years ago, Natalie Gelman has been almost studiously slow in releasing her sophomore release. The Ojai, California-based artist hasn’t exactly been hiding herself away though; she’s got some impressive notes on her resumé: she studied violin and attended the renowned LaGuardia High School of Performing Arts, was a soloist at Carnegie Hall, has opened for Bon Jovi on stage, and sung with Wyclef Jean. In between these she’s all the time performing in New York subways, and Gelman has applied herself admirably to gain traction and fans across the world, and to be able to work with her dream team of supporting musicians in the studio (as well as submitting winning entries to get the chance to perform with the aforementioned stars on stage).

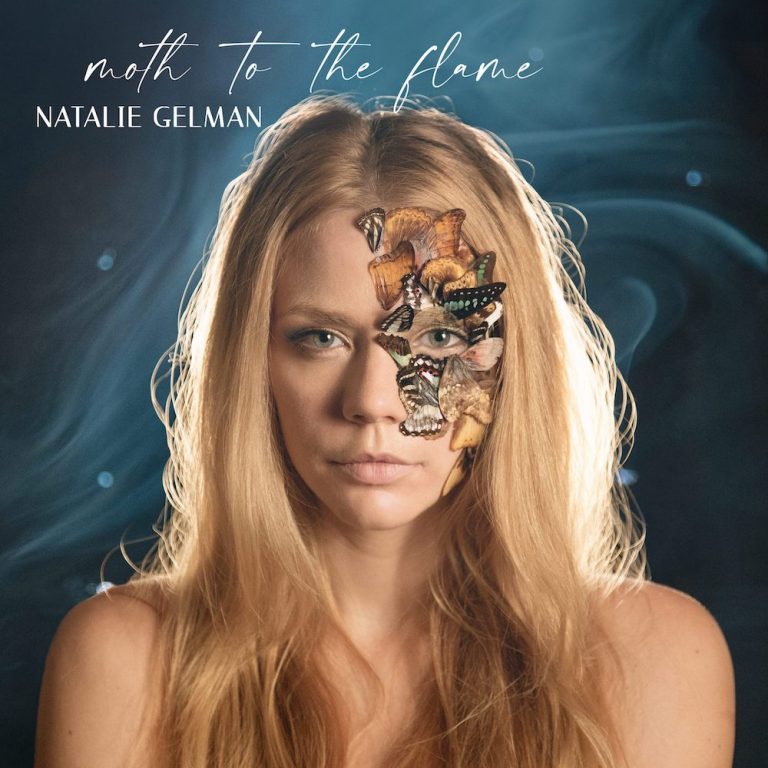

Moth To The Flame, then, comes with a softer texture than that on her self-titled debut album back in 2006, where Gelman sang her heart out like she was trying to capture your attention in a subway tunnel. Thanks to her hand-picked lineup of musicians (as well as the Grammy-winning engineers) Moth To The Flame sounds warmly lucent – almost to a fault. Banjo tickles the edges of “Some People”, giving it a sprightly bounce, while violin notes streak across “Summer Song” like wearying rays of sunshine catching your eye in the late afternoon. Closing track “Won’t Matter Anymore” languishes in a country smear, harmonica filling up the song to the edges as Gelman slips into her higher range.

The 13 songs on the album are pop, through and through, always catering to the predictable follow through of verses, choruses, and bridges. This is music that could play on a radio station any time of day and please the ear in passing well enough; innocuous and light enough not to ever have anyone’s parents tutting at a garden party or during a long drive to the country. At times, Gelman leans a little more to the country sound (the bobbing bounce of “Heavy, Heavy Heart”, the rousing bustle of “Love Let Me Go”), or dismay-tinged balladeering (the piano-led and and colourless “Unloving You”, the almost laughably overwrought and overdramatic “The Devil”), but amidst the surrounding material, it doesn’t ever feel out of place. Everything is neat and tidy (like a pop song often is), but as a consequence Gelman’s personality gets sunk into the mix.

Then again, a browse through Gelman’s lyrics can leave one all too understanding of why the backing music is always ready to take the focus. A big fan of the simile, she uses them liberally across Moth To The Flame, and, yikes, there are some clunkers that don’t hold up under any kind of scrutiny. On “The Way Things Go” the words are on her tongue “silent and ready to burn you like a shotgun,” whereas on the opening track and most recent single “Photograph” she “feel[s] like a photograph / like I’m almost real.” The aforementioned “Heavy, Heavy Heart” is just lazy, as she compares the titular saddened organ to a sinking stone.

On “The Devil”, Gelman goes for an ode to working hard and honestly, but mines the metaphor all the way through so she’s left drilling for air, her lyrics left making no sense; in the song she suggests that the fires of Hell are under some contract from an external gas supplier. Does Gelman think Lucifer is on a tariff for gas usage? On “I’d Do It Without You” the words become elementary school level: “Once upon a time from a big, big city / A girl takes a plane and gets lost in a pity / Finds herself in your arms, you tell her she’s pretty.” Considering the album was co-written with producer Charlie Midnight, one has to wonder where to point the finger of blame for these (and many other) lyrical tragedies.

But OK, sure, this is pop music, and it’s not out to muddy the water with complicated nuances or intricate detail. Gelman leans heavily on the idea of growing stronger throughout (not just on the almost achingly derivative “Stronger”), and it makes sense – how can anyone not relate to that feeling? With the tracks here you’ll get what they advertise on the tin, no song straying from its title in any kind of surprising way. But one just has to look to Taylor Swift for an example of how strong storytelling and mainstream appeal don’t have to be separate qualities; Gelman leaves the listener wanting for some semblance of personable substance.

The album is almost pleasingly mainstream though (special editions even come with a candle, just to drive home the titular marketing opportunities). Listening to Moth To The Flame likely won’t have anyone batting an eyelid if it’s on in some background setting, but the facade does wear away under any kind of inspection. And credit where it’s due: Gelman can write a hook that’ll wriggle itself into your head for a short while (“Heavy, Heavy Heart”, “Better Days”) and when she’s using the full range of her voice, it’ll catch you attention like a colourful tassel might catch a fish. She’s got the experience to please a crowd, but on Moth To The Flame Gelman can’t find anything of particular worth to say to her audience. And, after such a wait for the album to come about, that fact feels all the more disheartening and disappointing.