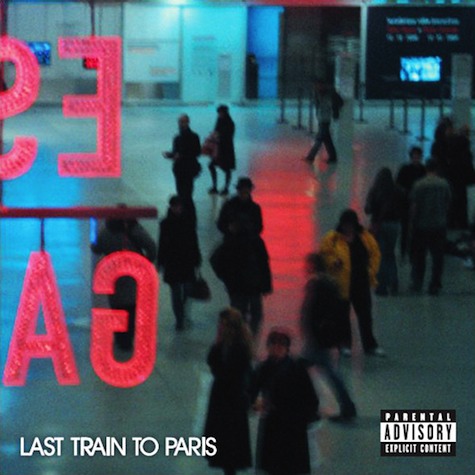

Diddy? What a joke. The harsh critic kicks in: he’s leeching life from Biggie’s ghost and propping Rick Ross up alongside him. What a joke. Take one look at the credits for Last Train to Paris and you won’t find Puff on a whole saddening lot of it. Some people say this would have been among the best rap records of the year had the ghost writers spit instead of Diddy, but they need not have worried. This album’s best moments all come from its plentiful guests, and with Swizz Beatz narrating a fair amount of the affair, Diddy’s presence is often hardly felt at all. That ends up being the annoyingly cool thing about this record: it plays as if Diddy had a bunch of his friends come over to hang out and an album randomly resulted. Crafted by a whole multitude of producers with that convenient “executive” label from Sean Combs on much of it (of the four singles released thus far, Combs produced not a one), this album is most likely the year’s greatest fabrication.

It’s an easy album to despise – Diddy has gradually been emplaced among the greatest villains of hip hop from a purist’s point of view. The over-sampling, Shyne’s arrest, the pop records, none of it has done Puff any more good than his constant name changing. The company he’s kept post-Biggie has never done him too much good either, and if the formation of “Diddy Dirty Money” was intended to curb that, it’s only resulted in a blanker façade. Yet, for the first time in years (really, years) Diddy’s music manages to sound alive, even through (in fact, largely thanks to) the decay of Comb’s persona. If anything, perhaps it’s the man’s personal problems which allowed this music to exist: even ghostwritten many of his verses manage to sound self pityingly personal – what we’re hearing isn’t likely a Diddy that Combs even realizes he’s letting us near.

As much of a joke as concepts usually end up consisting of on mainstream hip hop records, Paris essentially serves as a breakup album for Diddy. After an intro that sounds exactly as you’d imagine Diddy talking before his album would, “Yeah, Yeah You Would” catapults into a frenzied “how the 90’s would sound now” beat following a melodramatic Swizz intro. All of the material is equally dismissible and addictive; Diddy is marketing a product, but somehow came out with something organic and naturally progressing in the process. As polished as this product is, you can hardly call it radio friendly. It may be catchy, but much of it is too aggressive for traffic tune ins. “Ass on the Floor” samples Major Lazer’s pounding drums, “Hate You Now” borrows from Massive Attack, and so on. Above all, it all works as some sort of crazed mass, the songs work as a tapestry of a night influenced by one too many substances, scrambling for some sort of logic in a maelstrom. The songs are immediately listenable, but they throb forward and suddenly draw back rather than progressing smoothly – many songs even lack a discernible chorus. “Hate You Now” sloppily parries with its own confused feelings, “Strobe Lights” eerily swerves back and forth as Lil Wayne does his drugged out swag. Among the oddest of the bunch, “Shades” pairs a distorted, illogical Lil Wayne intro with Bilal and Justin Timberlake crooning, starting slow and ever so gradually throbbing towards explosive limits.

Principle among all the scattershot material is “Hello, Good Morning,” the ultimate realization of Diddy’s existence: what should be pointless noise coming together to create and irritatingly addictive song. Add in T.I., who takes the club-ready beat as reason to attack with a lightning flow, and you have what may well be the best pop rap song of the year. Really though, is this pop? Most accurately, this is “Diddy has enough money and influence to force out whatever album he wants,” and the delays and label hesitation only support the idea. So, perhaps the best question is in fact, what is this? It’s both the sleaziest album of the year and Diddy’s intricate fantasy world of mistreatment and vindication presented as a bizarre mass: he’s crafting himself into the figure he wants to be seen as (attempt to explain the grand show put on for “Coming Home” any other way), not fooled, we’re invited to watch the façade – and how much you’re able to tap into it entirely depends on how you’re able to stomach it.