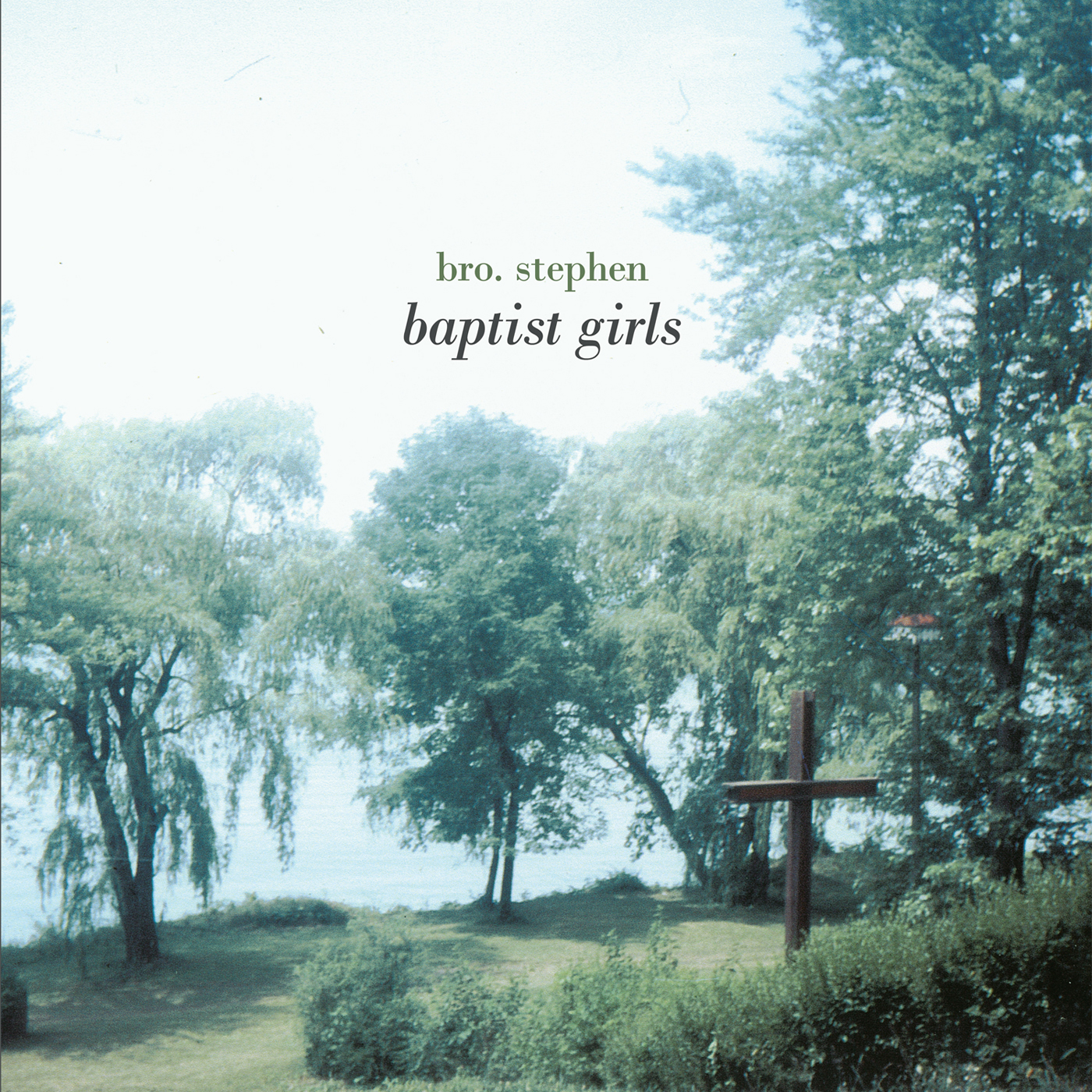

Christianity, and all the story and conflict that comes with it, makes for a great source of gravity in songs. Most of the time, singer-songwriters work it in as biblical references, religious imagery or spiritual themes. It’s not unreasonable to expect the same from Stephen Scott Kirkpatrick, performing as Bro. Stephen (pronounced “brother,” not simply “bro”) and his debut Baptist Girls, especially with those names. In reality, the album is almost devoid of explicit religious references, but the influence of a Midwestern Protestant upbringing is still there. It hangs over the music in how it has shaped Kirkpatrick’s emotional core, and every song comes from a place where sheltered innocence meets intimate troubles.

Each aspect of the album seems to aim toward invoking that specific kind of sorrow. Over twelve tracks, Kirkpatrick hits all the right notes to cultivate an ambient and sincere experience, centered around delicate emotions. On “Tears on Tape,” he works through the nuance of targeted sadness, while “Patron of the Arts” sounds as quiet and nervous as first heartbreak. There’s a childlike vibe to the sound and writing, not because he comes off as naive, but in the way it all seems so tiny and fragile.

Part of that is accomplished with the choice to go with musical understatement. Baptist Girls utilizes a variety of ambient noise and static to give songs a wide space, and Kirkpatrick sings with a very youthful softness. Most of the songs have no drum or percussion, as if even the smoothest jazz brush would be too harsh for the communion he’s trying to build. When it’s barely there, as in “Under Your Feet,” it adds a small measure of satisfying drama, which is intensified when the song shifts halfway through. He can do a lot with very little. The flip side of the atmosphere is that at its worst, tracks drift into uneventful sleepiness, but for listeners who feed on a song’s heart, the meal is filling most of the time.

The rest of that tender youthfulness comes from an on-the-nose lyrical style. There’s not a lot of abstraction or innovative poetry in songs like “Easy Love,” where a simple line like “Who’d have thought it’d be so easy to fall in love and out again,” is the central hook. On “Patron of the Arts,” it’s “I could never get close to you.” The beautiful frailty keeps them from being shallow lines and instead builds towards that sheltered innocence: it’s a statement of fact, no frills or attempt at romanticizing, just something raw and true. It’s not enough for the songs to be moving or melancholy, they also imply high stakes in the quietest ways.

It’s well on its way to its goal, but it doesn’t yet feel like it has reached its potential. Most of the tracks clock in at 2 minutes, which wouldn’t be so bad if they were written in a way that felt whole. Instead, they tend to cut off suddenly with a slightly awkward and out-of-step line, denying the listener the opportunity to wade in a more satisfying catharsis. It’s not surprising, then, that the best whole piece is the song’s longest and final track, “When You Find Out.” It’s one of the folksier songs on the album, zoomed in so closely to let you hear every detail. Kirkpatrick sings through a series of unfinished hypothetical statements – “If you don’t know where you’re going / If you think you might be lost,” – only capping it off after giving up on the song’s central, unrequited love.

In the closing minute, it also features the album’s only real moment of adult cynicism, which hits like a jaded response to Daniel Johnston’s claim that true love will find you in the end: “If you’re hoping love will save you, you best not hold your breath / By the time it comes to find you, you might have nothing left.” After so many encounters with the troubles of love, even the meek will grow some calluses.