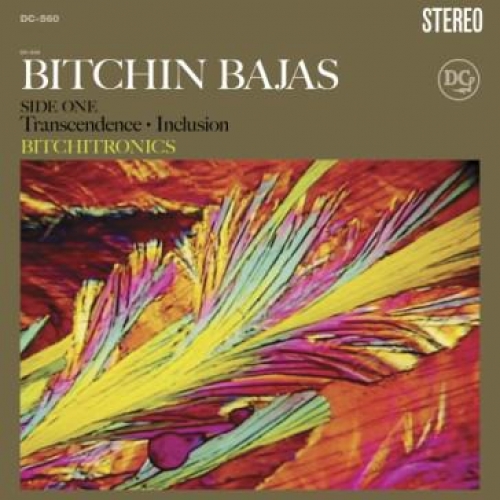

It’s difficult to discuss the latest record from Chicago experimental synth trio Bitchin Bajas without at least mentioning the inevitable influence of Brian Eno—and to a somewhat lesser degree, Robert Fripp. Eno has given us some of the most interesting and involved synthetic pop of the last four decades, while Fripp’s inimitable guitar work in bands like King Crimson and Fripp & Eno (imagine that) has set an unusually high mark for prog and art rock devotees. And although the decaying synths and unraveling rhythms on Bitchin Bajas’ newest offering, Bitchitronics, can feel at times more readily connected with modern day cassette drone aesthetics than ’70s synth-pop, the roots of the album and the band itself curl all the way back to Eno’s minimalist electronic experiments and, oddly enough, his exploration/breakdown of Muzak as a viable art form.

But even with their influences so readily apparent, Bitchin Bajas are not simply the sum total of their musical preferences or a mock continuation of Eno or Fripp’s legacy. The band carefully lays out spiraling patterns of synths and allows them to slowly fall apart in continually shifting parallel melodies. And though there isn’t much in the way of forward momentum on Bitchitronics, know that this doesn’t equate to a dearth of innovation, merely a determined examination of the negative space between decomposing sounds—and obviously the shadows of Tim Hecker and William Basinski’s oeuvres come into play here as well.

On opener “Transcendence,” the band merges whirring synth pads and crackling cassette static to form a haunting and curiously stationary cadence. Nothing is resolved—the deep-breathed notes simply exist, and any changes are modest and subtle. Even the occasional streak of unexpected guitar riffage doesn’t propel the song forward so much as it highlights the deceptively simple interchange of rhythms and synthetic composition inherent to Bitchin Bajas’ overall approach to music. To call it drone would be limiting and to call it catchy would be misleading, but there’s something remarkable about the casual unfurling of notes and the de-evolving structure that stays with you long after the track comes to a calmly measured end. “Inclusion” opens with a spry and slyly repeating synth line that seems as though a stiff breeze might carry it out your window, but the track tethers itself to the anticipatory part of your brain, which is always on the lookout for movement and resolution. And though the track doesn’t resolve in a typical fashion, the looping of sounds and the slow degradation of its admittedly undemanding rhythm acts as an aural narcotic, allowing the listener to become fully immersed in the Bajas’ ethereal repetition.

The band finds a curiously beautiful repetition on the languid “Sun City,” and they elegantly stretch it out until it feels like it’s going to evaporate into thin air — which is does a little after the five minute mark. There isn’t much push to reach any sort of conclusion, just a casual dissolution that seems plucked from the studio atmosphere. There is a tendency with droning, experimental music to have to ask the listener to listen past the surface noise and hear the patterns and rhythms that eventually make themselves heard through our own strained attention. And while this is a bit of a cop out–I mean, if the songs is good, you should be able to take it on its own merits–there is some logic to its application on Bitchitronics. On album closer “Turiya,” the oozing synths and ambient minimalism contort in shifting melodies and rhythms so light that, at times, they can barely be said to hold themselves together. But far from losing their way in these vast, echoing soundscapes, the band uses this negative space to explore even deeper layers of subconscious sounds. There is a sense of receding further into the circuital pathways of amplifiers, modulators, and filters in an attempt to separate the tangible aspects of musical creation from the internal idealization of what it should sound like. On Bitchitronics, Bitchin Bajas make the journey from unconscious creation to physical expression in a way that few of their electronic peers would understand. Brian Eno and Robert Fripp would approve, I’d imagine.