Compared to many of her peers, Annika Henderson’s artistic trajectory has been understatedly singular. Instead of clockworking between album cycle after album cycle – each emblazoned with a neatly contrived backstory – she allows herself to be taken to wherever her curiosity and pet interests lead her. This often puts her in transient, volatile situations, perpetually at odds of what she’s supposed to do vs. what she needs to do. At the root of it all stood her original goal to become a documentary journalist, an occupation that requires the practitioner to summon a voice to the urgency of now.

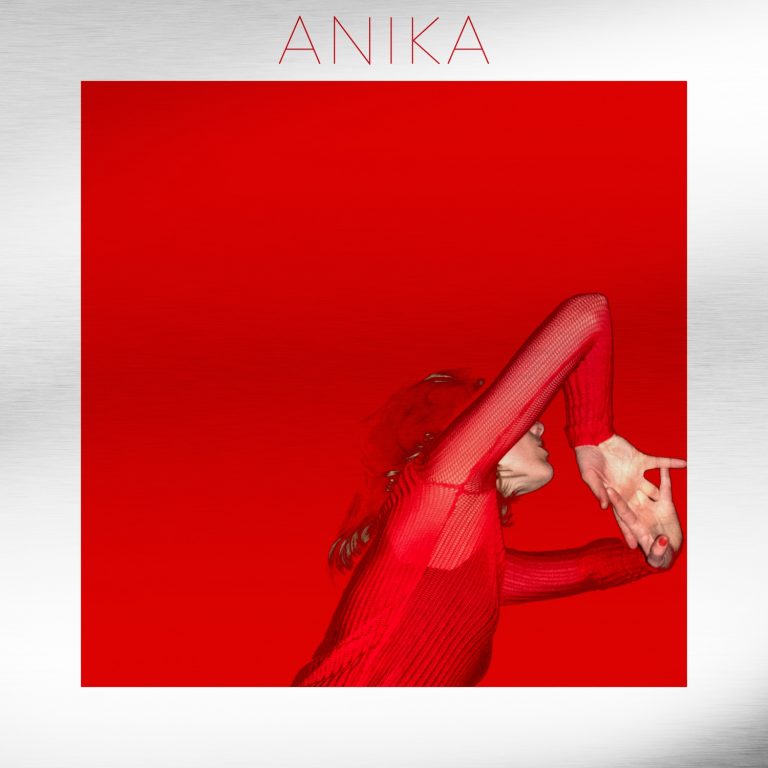

In Henderson’s case, this mindset has spilled over into other disciplines: photography, spoken word poetry, performance art and pop music, the latter under the moniker Anika. It explains why there is an 11-year gap between her debut LP and her latest album Change, without feeling as if Henderson has ever been away. Aside from releasing two terrific albums with Transatlantic post-punk outfit Exploded View, Henderson has nosedived into many different residencies and projects. From my own frame of reference, having interviewed her once for Drowned In Sound, she shed light on just a handful of them: one entailed feeding a computer entire books for an improv-performance, while another answer highlighted an artist residency in Iran.

That conversation really underlined the cerebral necessity Henderson’s endeavors merit: a willingness to be a prism for new experiences, ideas and awareness, and Change seems to be another cog in that headstrong inner pursuit. That being said, the album contains many of the familiar elements that typified other records Anika has been involved with. Of course, obviously, there’s that forever spellbinding, vapor-like voice of hers, which hovers around the music like a flame over a fuse. It beckons you like a wraith arisen from your subconsciousness, reducing all complexities down to a visceral essence.

Though the music is very much framed to noisy, post-punk and no wave affiliated music, there are hardly any hard edges on Change. Though often abstract and cryptic, Henderson’s self-possessed vocals never bend completely into the music’s gravitational pull. Her voice always remains aloft and graceful, the omniscient entity of Change’s ever-murky purgatory. The tribal minimalism of “Sand Witches” recalls Public Image Ltd.’s barren masterpiece The Flower Of Romance, giving ample room for Anika to give an inner monologue between her past and present self, neither of whom accepting of what became of the other. Henderson – who is half-German, half-British – sings with resolute fatalism: “You would like that we succumb / would like that we are eaten by the God-forsaken earth and our bodies leave no trace / just vessels to do your labor, thin wisps of smoke to do your bidding / who are you kidding?”

In every song on Change, it remains very ambiguous to who the “you”s and “I”s are referring to exactly, and that seems to be precisely the point. Henderson doesn’t seem content writing music as simply an emotional echo chamber: it has to be useful to the listener somehow, and that listener can be someone completely different. On the dub-inflected “Finger Pies”, she at one point sings the slightly meta lyric: “Every single word feels like a bomb / Theories you are a monster / That you hate yourself,” fully cognizant of the intrinsic power of words, and the potential mark they can leave on the human psyche. Change is a record that keenly pulls at the thread of black-and-white thinking and supposed monolithic evils, maintaining an even-keeled and unprejudiced lyrical center.

The withered, fatalistic “Never Coming Back” conflates sentiments of human neglect – whether they refer to a relationship or the natural environment – and was apparently written in the aftermath of reading Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which highlights the irreversible human destruction caused by pesticides.

The ambiguity of Change can be a bit frustrating at times: you kind of hope for something more tactile to hold onto, maybe a description of a scenery the listener can latch onto or even envision a backdrop to. But wishing for that would mean you’d have to go back to a place of comfort or familiarity. In the video for “Rights”, Anika takes an interesting stance on the notion of idealism and escapism, how being open and engaged to ideas relates to how those ideas manifest within our daily agendas. Oftentimes, they don’t, but there’s a grace in trying.

Though flawed, this record makes an admirably concentrated effort to disrupt the barriers of human estrangement and our defense mechanisms, using the malleability of words and sound to compel the listener – no matter how far apart in ideology or belief – to reach out from the other side. Anika seems well aware of that empathetic state on album’s title track, using the all too familiar “Knocking On Heaven’s Door” chord-progression as a Trojan Horse for a message of her own devices: “And we all have things to learn / about each other about the world / about ourselves.” Change seems more concerned with how the music impacts on a subliminal level than how it actually ends up sounding. Without those inner blemishes out on full display, that magnanimous intent could only go so far.