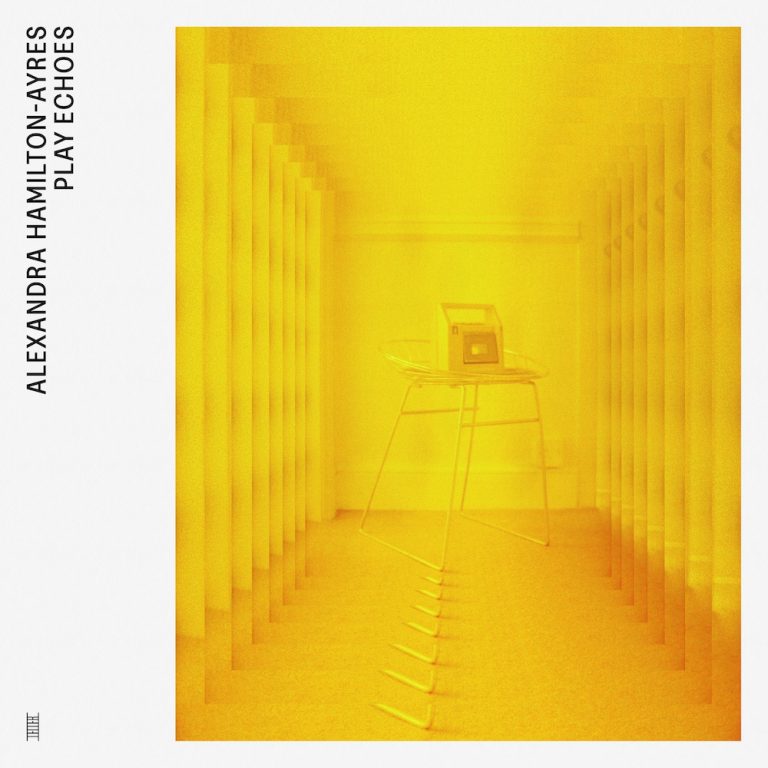

She didn’t know it at the time, but Alexandra Hamilton-Ayres’ started creating her new record decades ago when she was just three years old. Play Echoes began its inception after Hamilton-Ayres came across a recording of her younger self in conversation with her mother. Unearthed while packing up the family home before a move to France, it was the beginning point for Hamilton-Ayres creating her new album which went “to tap into memories and worlds that don’t exist anymore and capture them… I wanted to try and define what home, people, places and memories mean to me.”

A nostalgic record at its heart, on Play Echoes Hamilton-Ayres blends together electronic and electro-mechanical elements with classical accompaniments. Recorded with Her Ensemble (the UK’s first women and non-binary orchestra, which formed during the pandemic), the 12 pieces on Play Echoes move between stately classical pieces that would fit alongside a period drama, to burbling and murmuring electronic-led tracks that invite you to sink into them. They sound like the noises of rooms emptied of furniture and the hum of the natural heartbeat of a living place.

Play Echoes is at its best when it either allows the listener time to sink into Hamilton-Ayres’ music, and when it melds all the connecting elements together to hypnotising effect. The hypnagogic synths aside the hum of a harmonium on “Sept Douleurs” (named after the church in which she was baptised) give it a Max Richter-like tone, the strings adding expressive colour over the dark hue of the backdrop. The velvety piano on “Stone Stairs” is equally reminiscent of the German-born composer and pianist, the texture dreamy and soft.

Seven minute “Grenadine” is a late highlight, allowing plenty of time for the listener to sink into the murmuring synth pulses. Touches of piano and what sound like processed voices seep in and out of the mix, making for an inky burble; the extended time is what the music needs, and listening is like the aural equivalent of slipping into a warm bath and letting the water warm your body through. If more moments were given this kind of scope and space – the swirling “Watercolour” or scratchy “Unbound” (itself a sort of sibling-like coda to “Grenadine”) for example – then it would have made the listener more able to fall into the moods of the album. Like an empty room, sometimes you just want time to exist in it, and a few tracks seem to walk through locations instead of pausing for long enough.

A little trimming might also have helped the finer moments also stand out more. The courtly slide of strings and the gentle breaths of woodwind on “London 92” makes for a piece too rigid to leave an impression, while the solemn grey tone of “Doubts” is perfectly pretty but more a fog of colourlessness to pass through than much else. Every track might have a sonic element to pique your interest – the primordial simmering and call and response strings on “Channel”, the gentle dance of instruments on “Understanding Now”, the low-end percussive touches on “Unbound” – but compositionally they don’t always take you to a satisfying place in the end. Aforementioned “Watercolour”, for instance, which was originally written for the documentary Long Live My Happy Head, paints with plenty of colours as the title might suggest, but never quite reaches a satisfying head. Written in the first instance for a string quartet, it wants for more layers to heighten the spiralling swirls of strings, to double down on the angsty tone.

Hamilton-Ayres can still evoke those sorts of intangible feelings though, and there are a few amongst the tracklist that make the album worth the journey. “Stair Echoes” sweeps gracefully, and has a personal warmth embedded in it; it’s like taking a final walk through a now empty house you are moving out of. The final title track is something of a chilly afterthought after the album’s bubbling final third, but still beautiful in itself, like the kind of music you would play while taking a slow, contemplative walk through an autumnal setting. And at the other end of the album “Olympia”, with its pitter patter of synths dribbling down what sounds like an endless tunnel of light as Hamilton-Ayres’ three-year-old self talks to her mother. Where and when this and the other mentioned pieces were recorded matters little, because moments like these feel like home in one way or another.