One of the elements of The xx’s debut album that made it such a success was how fully-realized it was in sound and presentation. Much like Interpol’s Turn on the Bright Lights, The xx sounded like the work of artists far deeper into their career than they actually were. On Coexist, this trend continues, but there’s a layer of subtlety on the record that runs far deeper than that of their debut. The band has always been masterful at translating the emotional atmosphere of whispered bedroom confessions into music, but on Coexist, that atmosphere is so fragile, fleeting, and intimate, it often sounds as if it’s barely there.

Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s ‘Allelujah! Don’t Bend! Ascend! places them on the incredibly small list of acts that managed to return from a lengthy hiatus with a work that ranks among their very best. No one can craft the sounds of the apocalypse quite like Godspeed, and in a world that continuously feels as if it’s on the brink of total collapse, their return couldn’t have come at a better time. Don’t Bend! is a symphony of destruction – a proclamation of the end of the world that at once welcomes and fears it.

While The Weeknd uses an R&B palate to craft works of unspeakable menace and unsettlingly vivid moral decay, the closest thing he has to a sibling, How to Dress Well, pulls from that same stylistic pool in order to present a world of staggering loss, frailty, and beauty. There isn’t a single narrator this year that sounds more damaged than Tom Krell, but behind that darkness, there’s an undeniable sense that the void is escapable. Total Loss is a story of recovery, even in the face of unimaginable wreckage, and this elevates it from a work that’s simply bleak, to one that’s beautiful.

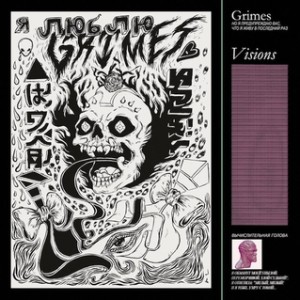

2012 was an incredibly strong year for music, in particular for albums either partially or completely electronic in nature. Grimes’ Visions is a stellar example of this digital renaissance – recalling everything from Bjork to Depeche Mode while simultaneously creating its own unique identity. It’s a pop record that’s as sugar-coated as it is off-kilter, and in that striking contrast, it ultimately finds its power.

Like many of the albums on this list, Kill for Love’s primary selling point is in its masterful grasp of atmosphere. It’s dark, dense, and often detached, opening with a cover of Neil Young’s “Hey Hey, My My (Into The Black)” that somehow manages to take that song’s lamentations and increase the tragedy of their tone exponentially. What follows is a record as indebted to the sounds of post-punk as it is new wave – layering the darkness of the instrumental work with a gloss of pop accessibility. Because of this, Kill for Love often works on two levels – initially pulling the listener in through its undeniably New Order-esque electronic sheen only to reveal its underlying sense of sorrow and loss the deeper we delve into its world.

Luxury Problems captures the dark side of rave-culture – the 4 a.m. come down on a night fueled by substance abuse and blaring electronic bass. It’s the moment where you’ve realized the party should have ended hours ago – the euphoria has metamorphosed into an inescapable depression, the music has turned menacing, and the people you loved only hours ago are now impossible to endure for another second. Luxury Problems takes you deep down into this darkness – peeling back the layers of the familiar stylistic tendencies of house music and revealing something frigid, murky, and threatening.

Like Sleigh Bells’ Treats, The Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy, and Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral, The Money Store isn’t notable because it’s loud, but because it redefines what loud can be. Its abrasion and its noise is constructed in a way you’ve never quite heard before – creating a volatility and unpredictability that adds immense power to the song work on display. Through its schizophrenic song construction, the band captures the sound of anguish, collapse, and desperation in a way that’s nauseatingly tangible. Much like a prison riot, The Money Store functions not as a means of escape, but of inflicting as much damage as possible before the inevitable return to confinement.