It took a special kind of American decline to birth God’s Country. Chat Pile‘s debut album combined direct political statements with mass murder lore and 80s slasher imagery. It embodied a landscape of spiritual suicide and expressionist madness, where Pamela Voorhees and a stoner hallucinating Grimace were as much symptoms of a necro-society as homeless people suffering from Scabies and mass shooting victims. What aided the album was a grotesque sonic palette of post-hardcore staples: drums that sounded like Big Black’s machine-beat, spidering industrial guitars and vocalist Raygun Busch snarling as if trying to challenge The Jesus Lizard to a face-off. The record even had a bizarre sense of humor, teetering on the verge of camp.

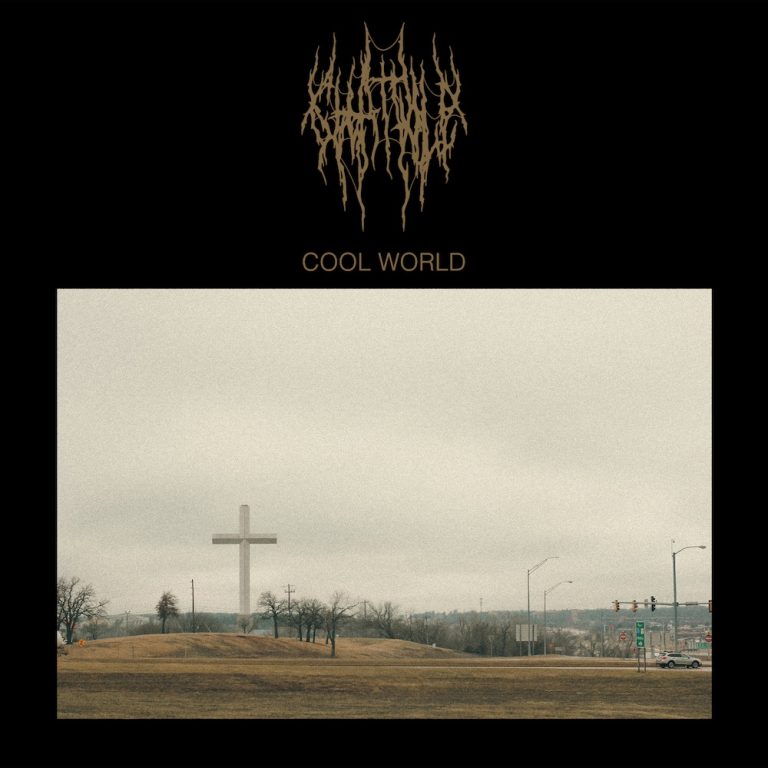

With Cool World, Chat Pile have to confront the thankless task of following up this monolithic debut. Instead of playing it safe, they have chosen a standard staple of follow ups: they go darker. Where God’s Country had an ironic distance to its subjects and their actions – Busch performing their atrocities in exaggerated tone or functioning as god-like observer with moral inclination – here the storytelling unfolds in abstract vignettes. Additionally, there’s a new groove in the rhythm section’s style, a newfound appreciation for blues tonality, while the guitar parts are further removed from the classic rock’n’roll imagery present on the debut now resemble the strange incoherence found in the catalogue of The Residents. In this, the record leans towards the demented new wave that marked 1980s American counter culture, such as Pere Ubu or even Sun City Girls.

The record’s centre alludes to that sardonic avant-garde fracturing of national nightmares. “Camcorder” and “Tape” seem to fold onto each other, with one a tool to produce the other. “Camcorder” is lumbering and drenched in doom, as Busch imagines a heartless perpetrator: “Watch it change in my hands / Watch the whole goddamn world change / Everything that I know, completely obliterated”. The song slowly fades out to the ambient sounds of guitar strings reverberating, as the drums march on.

“Tape” picks up with the perspective of an innocent bystander, who stumbles across foreign horrors: “We shouldn’t have gone onto that property / And even still further into the house / We should have let someone know and they could have handled it / Someone else could have handled it / They made tapes / It was the worst I ever saw”. This horror scenario isn’t far from reality, given the anecdotal evidence surrounding John W. Gacy’s case. Instead, it magnifies ideas of a suburban nightmare that develops from the tension within American culture. The perpetrator feels as powerless outside of his actions as the innocent witness that finds the documentation thereof. The power lies merely within the objects that mark the proof of both their actions: the witness becomes part of it.

The strange metal of “The New World” enforces these images of complicity even further. If this ‘new world’ is the United States, it’s unclear whether the individuals that the narrator describes as being “dragged kicking and screaming out / Into the new world” are future settlers that are forced, or the native population being carried away to allow for re-population. Other images in the song seem almost fairytale like, with a speaking skull that says nothing but the truth and a bipolar living experience: “To be lost, to be whole, to be bought, to be sold / To lose hope, to lose God, to find hate, to find law”.

It’s possible to contrast this with “Funny Man”, the Cool World track that seems closest in aesthetics to Pere Ubu. Over spidering guitar lines, Busch imagines an individual that is handcuffed to societal norms and familial standards, partaking in christian rituals and filling his father’s shoes. Especially interesting is the focus on a Joker-like entity that embodies culture’s violent tendencies: “Thе wicked jester is dancing and clapping / As my big, strong hands kill the people they told me / There are times that I can almost believe it / I can almost imagine I was meant to do this and be here”. The focus seems quite intentionally to be on the abusive cycles within army culture – as older veterans die slow deaths, they direct their sons into the arms of the military industrial complex. Rinse, repeat. The focus of both “The New World” and “Funny Man” is in how landscapes are inherently tied to warfare – psychological and physical, ultimately cannibalising their own population.

A different take on the military is the record’s standout song, “Masc”. It’s the sole hit here, a merciless punk drudge that portrays a confused relationship: the narrator is locked in a hopeless situation of powerlessness, directed to ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’. As they watch their significant other engage in all sorts of domination rituals (“I caught you laughing again / I know I’m lower than scum / I need to keep my mouth shut / Before I look fuckin’ dumb”), they grapple with the mantra of “Trust and bleed, I / Trust and bleed, I”. Busch pulls off his best performance on the record, employing a woeful, depressed tone during the verses, before finally exploding in the last part of the song, hauling his desperation in sharp bursts as he repeatedly yells “Cut me open”.

Much of Cool World seems influenced by the ideas of Rousseau’s The Social Contract (with opener “I am Dog Now” a direct reference to it). Summed up in layman’s terms, the work argues that ‘might is not right’ – Rousseau postulates that the ruling class has to find a means of authority that is compatible with the individual’s freedom of choice, in the end obeying themselves over their leaders. This hypothesis leads to democratic idealism – from ‘the will of the people’ to ‘equal laws for all’, ‘wealth equality’ and ‘collective self-rule’. If you will: proto-socialist politics.

Given that the work was released during the middle of the 18th century, it’s depressing to confront the world of Cool World, where the the nation is enslaved under the will of one power and individuals are locked into pre-determined behavioural patterns, with the sole escapism existing in violent forms. Rousseau believed that it wasn’t merely their representatives, but the people themselves who wield power through their execution of democracy – yet in a two party system that depends on inequality to further its own wealth and superiority, the collective becomes comprised of disfigured souls. And worse yet, this also leads to a nation that isn’t just conquering, but actively killing.

With all its depictions of veterans and military structures, it’s “Shame” that’s the most harrowing song: “In their parents arms, the kids were falling apart / Broken tiny bodies holding tiny still hearts / There are myriad ways to destroy human skin / Red flesh exposed raw over and over again”. Consider the many images we witness on social media every day from Gaza, and the soul shattering number of dead children – yet our ruling classes use language such as “[ending] up in very difficult waters” to describe their process of further removing protected status from civilian sites. Busch confronts this language with his own moralism: “It stung hot in my eyes, the illusion of justice / It burned deep in my face, felt unbearably selfish”.

Busch has been criticised in the past, for employing tired tropes or focusing on death metal clichés, but he is one of the most honest lyricists and performers in the current day American rock canon. He never pretends that his posture is more than performance, that his subjects are characters witnessed on VHS movies and political rallies. Likewise, he uses different tonal qualities of his voice to explore their existence outside of well adjusted, suburban middle class circles. They’re often freaks of culture, the product of systems that chew them up and spit them out.

If there’s a criticism that could be directed at Cool World, it’s that the album lacks the narrative flow and atmospheric variety of the debut. God’s Country was more nuanced in playing with dynamics, including a spoken word piece and employing the band as storytelling device (such as when “The Mask” narrates the gun of a mass murderer through its drum beat). Cool World occasionally has a formlessness that drowns out some of the lesser tracks in its aesthetic. This isn’t expressly a criticism, but considering a track like “Frownland” – which functions similar to Big Black’s “Kerosene” yet lacking its climactic chorus – it becomes clear that Chat Pile are focusing on expanding into a gradual abstraction of what their core form persists of: further into strangely spidering guitar melodies, with Busch gurgling over bluesy rhythms. The explosive, libidinal push-and-pull of grooving thematic structures inherent to God’s Country – that can be observed in the film that gave Cool World its title – is at times ignored in favour of focusing on jagged edges.

Still, the record is in no way a fall from grace of drop of form. It’s the uglier, more poetic and brooding cousin of the debut. A proof of sheer willpower, yet still a transitional work of a band growing comfortably into their future.