You always knew you were fucked up! From the time you were a kid, how other kids would look at you, your twisted reflection in the mirror. Deformed snakes as limbs, with carcass skin and broken frame of ribs. Showers of spit and fists brought you here, this pit where you attempt to discharge the thought, the understanding that your daily life is now a nightmare. That you are stuck in here, joke of god, nature’s mockery, screaming flesh factory of bile. You do not eat for days, at night you find yourself rehearsing for your monologue of filth, retracing every unwashed body traced by your tongue, every rite of masturbation, every scream of blood and tears fuelled by oppression and by violence. You revolt against what you’ve been given, sedate your mind and haul up what’s inside of you simply, because, it feels better, than this. Because then, things are quiet. For a second, or a minute.

Until god comes back and screams you down.

We know this, cause we’ve been there, once or twice. Seen what they’re capable of, and felt those tears of reality rip wide open. What’s beyond the skin, beyond the mind, beyond the light that shines: limitless boundary experiences, existence on the margins.

Yet we are still: here.

When Uniform‘s Michael Berdan opened up about his eating disorder this summer, he ripped open a discourse that is all too often reserved for the shameful moments of soul stripping, social media awareness and self-help group talk. He confronted a reality that, for many people, is one carried in silence. Berdan had been open about his alcoholism and struggle with mental health in the past, but reading his intimate insights on the malaise that this struggle brought with it felt like he let light into a hidden burial chamber in a larger structure. I hope, to whatever lord preys on our pain, that this openness has given Michael a lot of solace, and paved a path forward.

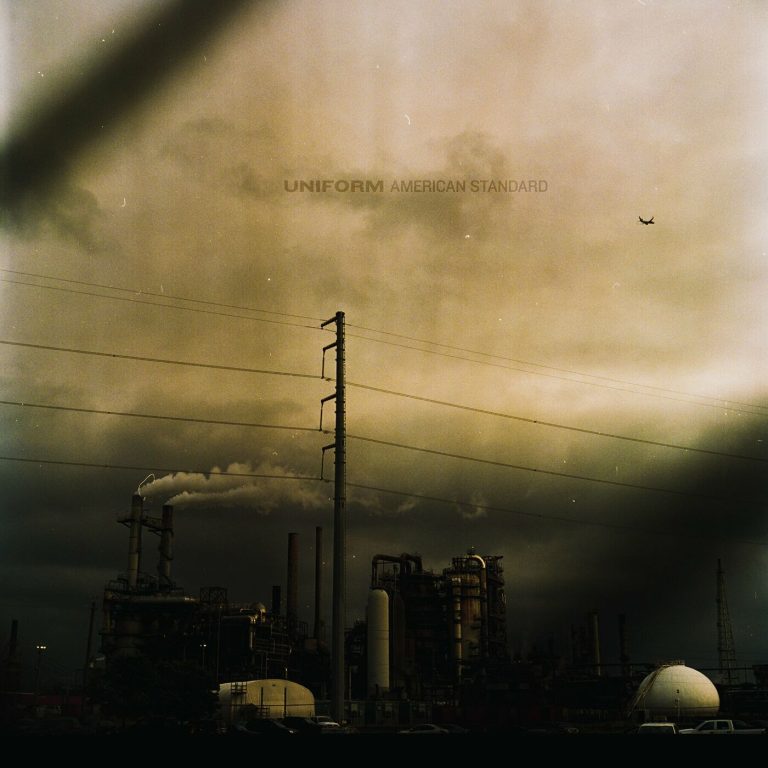

But most of all, I’m scared of his group’s new album, American Standard. In about 40 minutes, and only four songs, Uniform have leapt across the divide of genre boundaries and their prior figuration to create a brutalist, industrial manifesto of apocalypse prayer, caked in the colour of puke.

Yes, this is a concept album, marked by raw, unhinged power of delirious brutality, often so unremitting that it hurts. Inspired by modern American horror literature – Berdan cited B.R. Yeager and Maggie Siebert as direct influences – American Standard allows Uniform’s frontman to measure his own history against the make-up of the fading landscapes of the US, bereft of empathy or humanism. When Berdan opens the album with a yelled chorus, over and over shrieking about the meat around his bones, this constant barrage of hatred echoes in the emptiness of barren rooms and lack of love. It reflects Einstürzende Neubauten’s “Halber Mensch”; their post-religious observation of man as divided entity, whose second half has become merged with technology, wires and media: bodies as a part of urban architecture. Berdan extends their gaze beyond existence in society: he negates idealism.

As the song explodes into a maximalist composition of pounding sublimity, Berdan focuses on an insect in his hand – incapable of consciousness. “Insect in my hand / It knows only my palm / I know it can think / It needs to understand / I am all it will ever know / I am all it will ever see / I am all it will ever touch / I am all it will ever love”. The song continues to build in volume, reaching the cosmic qualities of Swans and Ramleh, as the cruelty of the depicted situation manifests. Across its 21 minutes, the song’s exhausting, glorious, acidic radioactivity bleaches any preconception of what Uniform are or could be. It’s an anthem of despair, something few musicians could even dream to touch. By the time it explodes into its final movement, there’s no doubt American Standard is a record for eternity.

Following track “This is not a Prayer” is a metallic cross of post-punk and black metal. With its Darkthrone-like guitar barrages and pummeling tribal drums that somehow seem to gradually multiply past the point of physical possibility, it feels like a satanic mutation of Johnny Rotten’s PiL. Berdan’s screams of his one true wish – to not be forgotten – give him the figure of a starving monster, a creature deprived of what keeps it alive, yet somehow still breathing, pushing past its point of physical existence.

It is followed by “Clemency”, which somehow floats in like ancient music recollected through a dream (possibly recalling works by The Caretaker or Imperial Triumphant – maybe even the obscure blackened noise act La Torture des Ténèbres). But then the track explodes into a barrage of doom metal, with Berdan shouting “You can’t change / Who you are” and “You can’t begin to take back / What you have already done” – it’s demonic and bludgeoning, shifting into the portrait of a family person trapped within his own home: “God of the living room / You’re swollen in your seat / You can control these four walls / You can decorate them with filigree / You can change their colours / You can puncture them with nails, with hammers / You can puncture them with fists, with bullets”. The image, of course, is as much a symbol for a person’s social structure as it is of their own body.

This is where Berdan’s literary influences come in. Maggie Siebert’s writing sees the individual as caught within the confines of systems which, ultimately, strangle their ability to function properly – if not from the outside (of capitalism, family, pornography of the soul), then from within their very digestive tract: their ability to overcome trauma, to find optimism, to keep the things down that were put inside of them. Yeager’s tone is even more consequential: if a world is that broken, it pushes individuals into the virtual shadow realms of online forums and drug consumption – alternative stages that serve the theatrical production of disgust, and the performance of moral decline.

On American Standard, the reflection on the American landscape becomes poignant: Berdan oftentimes calls out to god, or recalls the rituals associated with faith. These calls to a higher power – or reminders there is no one to answer your pleas – show the reality of a country which has given up on dreams, and is only content to churn more bodies into a merciless machine. Of course, with us being sensitive and sentient beings, any realisation of this process must ultimately mean insanity, illness, a rejection of the capital our functioning bodies are seen as.

On the album’s final track, “Permanent Embrace”, this comes with classic imagery from J.G. Ballard’s playbook: the sexual connotation of a car crash. “Dad tells a story of two cars crashed together / It’s not ironic, it’s what they wanted / It’s not a mistake, it’s what they wished for / A single form, exchange of steel and glass”. The image becomes a metaphor for a dysfunctional relationship, built on mutual trauma – and it extends over time: “Twenty years later, I tell you the same fucking story / And your eyes, your eyes betrayed your terror / And you found, you found my love appalling / And we found complete and total negation”. The song explodes into an archaic, blackened metal track with semi-religious nuances via a synthetic choir, ending the album on a grandiose note of despair. The one single option that could possibly lead out of this – the caring embrace of another – ends in just another moment of defilement and rejection, disgust at the protagonist and the fabric of their meat.

It’s taxing to experience, American Standard. There’s a reason why its vinyl iteration comes in the colour of puke. It is, in every way, a transgressive, brutalist piece of art. In its unbelievable size and musical scope, it holds unnerving power, channeling the mind of someone suffering from this infliction Berdan sought to capture in disturbing forms. And yet, it also instills hope. It shows the artist willing to open up and reveal himself, transform his pain into an experience close to Georges Bataille: a destabilisation of all things, high and low, through a complete reduction on matter. His term of consummation – the spending of any excess economic expenditure into sumptuous monuments of excess, sexual or violent – seem to fuse with Berdan’s ideas of the body. Bataille found his monuments in war and fetishised sex – rituals permissible only within rejection of christian values – while Berdan’s songs of hanging meat, disgusting sweat and necessary vomit chronicle the opposite to the healthy and performative bodies capitalism demands.

I’m not sure if this is a good representation of this work, or merely an attempt to intellectualise a process of disgust. But no matter the interpretation, American Standard holds the power to save lives. Within its poetry of horror, there is a deep humanism that allows for the question of healing – to at least attempt to find the energy to revolt. If the body upheaves its nurture in the light of smothering structures, then maybe we need better structures, and more love for those whose struggles we are told to barely glimpse. Maybe we need to build a better world. Or, simply, let light in for others to see us, naked, retching, out of breath.