An abstract artist and friend of mine used to get annoyed when viewers would say that they could recognize a cat or whale or Abe Lincoln’s face in his painting. He would suggest that they suspend scanning for familiar elements and instead embrace a non-associative experience: be disoriented, rather than reductively forcing the piece to align with conditioned modes of perception and interpretation.

Instrumental music often encounters similar responses: that melodic fragment reminds me of The Beatles, that drum part sounds like Meg White, etc. That said, some music lends itself to metaphoric consideration, which is a bit different than relying on simplistic comparisons. Free jazz, for example, is inevitably encountered as a commentary on the intersection between fate and volition, determinism and choice, structure and transcendence. Vacillations between maximalism and minimalism depict life’s alternating vastness and cluttered-ness. Succinct and unrestrained passages are contrasted. Archetypal references offset and complement each other. Such musical forays are born of an instinctive awareness of life’s myriad energies and in turn invoke them, serving as ontological and existential manifestos as much as purely aesthetic experiments.

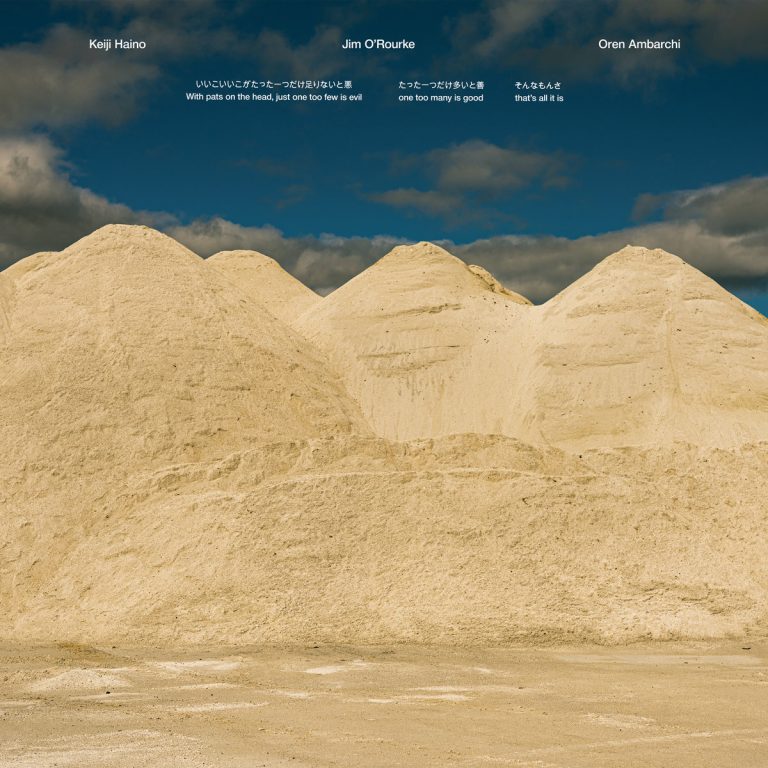

Having worked with one another on numerous ventures, including 2012’s Imikuzushi and 2022’s “Caught in the dilemma of being made to choose” This makes the modesty which should never been closed off itself Continue to ask itself: “Ready or not?”, Oren Ambarchi, Keiji Haino and Jim O’Rourke offer their latest LP, With pats on the head, just one too few is evil one too many is good that’s all it is (in addition to manifesting excellent music, the trio get the award for lengthy titles – both for albums and for songs within them).

Throughout the set, the three musicians make use of their affinities for rock, jazz, and a variety of atmospherics, maneuvering soundscapes at once ethereal and earthy, celestial and mechanistic, purgatorial and dystopian. With pats on the head shows each musician is at his most eloquent. The trio are keenly responsive to each other, a listener transported by their complex interplays.

The first track spotlights Haino’s accent-leaning percussion (snare) and O’Rourke’s spontaneous guitar excursions, moving from the austere to the busy. Haino avoids time-keeping while O’Rourke eschews defined riffs, opting for centrifugal flurries. With track 2, eerie tones are investigated, alien resonances that would seduce Mark Fisher and wouldn’t be out of place on a hauntology compilation. Percussive elements (Ambarchi) are more rhythmic than on the first track, undergirding a series of electronically generated moans, drones, and flourishes (O’Rourke). The latter half of the third track brings the project’s percussive aspects into the limelight, Haino and Ambarchi engaged in a compelling drum duet, collaborating and polarizing, oscillating between classic beats and rolls and a more random/ambient orientation.

With track 4, a sustained monotone waxes and wanes as drums pivot between time-keeping and decontextualized (disembodied) accents. The musicians pursue individual trajectories but with patient attunement to their bandmates’ subtle shifts. Toward the end of the piece, they converge, rhythm devolving into sandpaper drones that point to both consternation and playfulness. The 22-minute track 5 continues this line of research, Haino launching with off-tempo and staccato strums while O’Rourke wrestles with a six-string bass. The piece swells into a celebration of flux and stasis. Echoes of love and rage, Dionysian and Apollonian ritualism, the frenetic and methodical. In synesthetic terms, there’s blue and red, dashes of yellow, dollops of brown. Circles emerge but also brittle edges. Acute vertices erupt into sky; shrinking rooms are conflagrated by mesmerizing flares.

The 23-plus-minute track 6 is similarly a fete of noise, melody, rhythm, arrhythmia, rogue artistry, and adrenalized triothink. Midway, the piece ascends, drum beats and electronic swaths woven into seductive pastiches. Sprawling noise radiates a visceral and cognitive purity. In zen terms, this is the thrum of the spacious mind. Also, the musicians’ ability to sustain shamanic crescendos for extended periods is no less than alchemically tantric, the listener guided into the unknown, discombobulated (in a way that would please Rimbaud and Morrison), obliterated, subsequently enlightened, and brought back. Maybe.

With the closing track, the musicians return to terra firma. Languid sounds echo and mingle, inching toward crescendo, the piece then boomeranging back toward sparseness, quiet repetition. The track does indeed morph midway into a denser sound, Haino’s distorted guitar blasts in sync with Ambarchi’s militaristic drum beats. As the piece nears completion, it slows, bogs down, lurches toward stillness, singularity. Distorted notes linger, conjuring flashes of Sunn O))), Kali Malone’s Does Spring Hide Its Joy, Neil Young’s soundtrack for Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, and Jarmusch’s own band Sqürl. The track culminates with gorgeous jumbles of serrated guitar that sizzle, pop, and sputter.

With pats on the head is an entrancing exploration of individualism, communality, and the rising and passing of energies. Occasionally skeletal, more often ecstatically maximal, the sequence reminds us that the moment at hand is inherently devoid of the narratives and judgments we customarily drag into it. Ambarchi, Haino, and O’Rourke express themselves from that unlimited locale, that eternal emptiness. Goodbye, inner critic. They’re free, curious, pursuing connection, discovery, a kind of mystical pan-union. Ambarchi, Haino, and O’Rourke teach us: life and art are like sand mandalas – uniquely precise, stunningly impermanent.