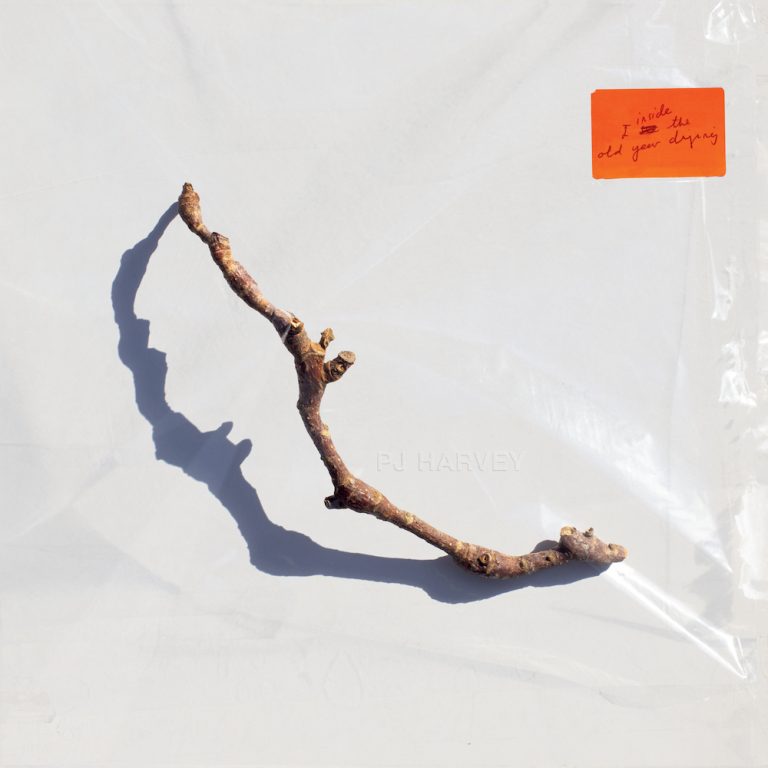

“I was quite lost,” says Polly Harvey of the period that produced her new, 10th (and first for seven years) LP I Inside the Old Year Dying. “I really wasn’t sure what I wanted to do: if I wanted to carry on writing albums and playing, or if it was time for a change in my life- ‘OK, I’ve done this for a long time. Do I want to carry on for the remainder of my life doing the same thing?’”

It probably doesn’t come as a huge surprise to hear that Harvey, burnt out by a gruelling year-long world tour in support of 2016’s The Hope Six Demolition Project, found herself in a rut. There hadn’t been a single whisper of new studio recording since then – she had worked diligently on music for the stage and for film and TV soundtracks and, of course, had been working on the beautiful, strange Orlam, her poetry collection that published last spring.

Sprinkled in the middle of this period was a delicious reissue campaign of her entire back catalogue with accompanying demos albums – manna for the PJ Harvey fan. But you got the sense that there was something of a shift happening in real time for Harvey; the album-tour-album cycle had been resolutely broken and she was pursuing her artistic urges in oblique and sometimes obscure new directions.

It wasn’t the first time Harvey expressed doubts on her future in the music business – she told Q magazine in 2001 that she almost gave up music to retrain as a nurse in the low period between 1995’s To Bring You My Love and 1998’s Is This Desire? – but the move towards writing, particularly on such an all-encompassing work as Orlam, had an air of finality about it and the lengthening gap seemed to support a sense that Harvey might just be done in terms of recording new albums.

So seeing studio photos by Steve Gullick uploaded to her Instagram account in February 2022 was, certainly, an exciting and surprising change of pace. As it turns out, Harvey was in the thick of recording her new album at London’s Battery Studios with long-time collaborators John Parish and Flood. She describes how the songs “fell out of [her]” within three weeks, and indeed the music has both an immediacy and a haziness that suggests a conception that is far from studied and rehearsed.

What is a PJ Harvey album in 2023 going to sound like? Harvey has made a career on sharp turns, unexpected diversions, the persistent search for new ways of singing, writing, recording. Hope Six, for all its lively garage-rock swagger and vivid sketches, felt somewhat distant and cold and, following on from its counterpart Let England Shake, seemed to occupy a similar kind of space thematically and in terms of performance – Harvey’s voice high and reedy, the outside narrator observing the scene without opinion or emotion. The last time Harvey felt such an innate need for something new was on 2007’s White Chalk, where she ditched the guitar for the piano and traded the raw energy of her previous records for an album of strange, austere, gothic ballads of autumnal beauty. She sang in a new, plaintive voice – her “church voice” – and wrote songs that were somehow both thrillingly different and offbeat but made sense within the Harvey oeuvre.

I Inside the Old Year Dying, perhaps not coincidentally then, most closely resembles White Chalk in terms of its mood and style – perhaps incongruously released in July, it is certainly an autumnal listen; Harvey sings most of it in a higher register and there is an elegant, restrained intimacy that recalls some of White Chalk. But it does not share the same piano-centric DNA and, indeed, some of it also recalls the ramshackle folksiness of some of the deeper cuts on 2004’s Uh Huh Her. In fundamental terms, it trades Let England Shake and Hope Six’s looking-outwards philosophy to focus firmly on the interior. “I instinctively needed a change of scale,” Harvey has said. “There was a real yearning in me to change it back to something really small – so it comes down to one person, one wood, a village.”

The “one person, one wood, a village” refers to Ira-Abel Rawles, the central figure in Harvey’s poem Orlam, which forms the basis for the lyrics of I Inside the Old Year Dying. Ira is a young girl growing up in the fictional Dorset village of Underwhelem, surrounded by a peculiar crop of villagers and family. Orlam is a story of awakening, the tension between the natural world and physical reality, and the inevitability of the passing of the seasons, all of which are loosely evoked throughout the album.

The Harvey of 2023 is no longer an artistic compartmentaliser, which is why it might take some getting used to in understanding that the album occupies the same artistic terrain as the book. The filmmaker Steve McQueen told Harvey during the Hope Six era: “Polly, you have to stop thinking about music like it’s all albums of songs. You’ve got to think about what you love. You love words, you love images and you love music. And you’ve got to think, What can I do with those three things?”

It’s not necessary to know Orlam to be able to enjoy I Inside the Old Year Dying, but such is the esoteric nature of the work that, as song lyrics, they are far more oblique than we’re used to from Harvey. As a lyricist, and indeed as a musician, Harvey has always been pretty direct. The deceptive simplicity in her work, both lyrically and musically, has always been her superpower. I Inside the Old Year Dying marks a significant change in this regard – written in Dorset dialect and sung again with her natural accent (yes, recalling that “church voice” of White Chalk), the text is an allegory of childhood, adolescence, the natural world – it’s an evocation of the English countryside and rural magic realism.

There are thematic threads that weave in and out – the shadowy symbol of Wyman-Elvis, who is both a Christ-like mythical figure and a ghostly spectre (“are you Elvis? Are you God?” she sings on the fragile and folky “Lwonesome Tonight”), the dreaded feeling of starting school, and the haunting refrains of “Love Me Tender” that shift in and out of several songs. It’s not something that the listener is particularly able to pin down, and that appears to be the point – I Inside the Old Year Dying seems not to be an album that you are supposed to “understand,” but instead one that you feel. A lot of the songs are about memories and delving back into the past, and the music and production – which is not rough in the sense of Uh Huh Her but not polished like a Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea – perfectly captures the distance, both physical and mental, of memory and the passing of time.

The Dorset dialect lends the album its unique poetic sensibility and also contributes to its slippery feeling of unknowability; “Quaterevil takes a wife / chilver meets her Maker / as the grindstone turns the knife / o’er Eleven Acres,” scans “The Nether-Edge.” It’s beautiful and strange and not your usual PJ Harvey lyric. But, just as readily, she emerges with imagery as familiar as “Pepsi fizz / peanut and banana sandwiches.”

Some songs have a formative, Beefhearty vibe, from the rough-hewn guitar roll of “Seem an I” (translated as “Seems to Me”) to the ramshackle chaos of the delivery of “Autumn Term”, but anyone familiar with Harvey’s soundtrack work post-Hope Six – particularly All About Eve – will recognise the restrained elegance in some of the chord structures of songs like “Prayer at the Gate” and “Lwonesome Tonight”. I Inside the Old Year Dying is an album that seems to hinge on these kind of fault-lines – between the corporeal and the imagined, the poetic and the prosaic, the bridge between childhood and adulthood. Of “life and death all innertwined,” as she keens on “Prayer on the Gate”.

Musically, the deft fusion of the delicate and the hearty reflects Harvey’s thematic explorations; the production is full of strange quirks, whether found sounds or unusual effects that are sometimes inserted and not repeated. The effect is that the music feels both hazy and alive, evoking the Orlam world in its strange splendour.

Another key to the sound is the use of male vocals not just for contrast but for poetic resonance, and the way Harvey employs the voices of Parish and actors Ben Whishaw and Colin Morgan is haunting and rather beautiful. The interpolation of Whishaw singing a segment of “Love Me Tender” in the foggy magnificence that is “August” is nothing short of stunning, while Parish’s crazed singing with Harvey on “Autumn Term” has a bizarre, nightmarish vibe that captures that first-day-of-school dread – “I ascend three steps to hell / the school bus heaves up the hill.” Morgan, meanwhile, provides the folk-horror chant that “A Child’s Question, July,” is built around – all Wicker Man ritual, with its “twoad”-licking and rural dance around the phallic Ooser-Rod.

For an album that evokes childhood and adolescence so strongly, I Inside the Old Year Dying makes use of some of Harvey’s most girlish singing – the beginning of “Seem an I”, for instance, is sung as if she were a girl singing to herself at the bus stop. It then morphs into its Beefheart roll, and it also puts me in mind loosely of “Heaven”, one of Harvey’s earliest recordings, that later emerged as a b-side in the White Chalk era. There is that same innocence of sound, the simple and joyful guitar pattern (although slowed and rougher), and the murky merging of the past and the present. In some ways, it makes sense on such a record that Harvey might subconsciously revisit something from the past.

The Beefheart influence found in so much of Harvey’s work can also be detected, for me, on “Autumn Term”, which seems to heave and creak like the bus in the lyrics; it’s sung in a deranged yet contained A Woman A Man Walked By style. “The Nether-edge”, meanwhile, begins with a disembodied vocal effect; it has a strange, strident beat that recalls Pink Floyd’s menacing “One of These Days”, before becoming something altogether jauntier.

“I Inside the Old Year Dying” is a classic Harvey acoustic guitar D-minor stomp with beautiful, reverb-drenched piano piercing the fog; “All Souls” is a melancholy dirge, one that starts so purely and softly, with one of Harvey’s gentlest and loveliest vocals, before the arrangement builds into a heavy hymn. “A Child’s Question, August” is both a deceptive and appropriate trailer for the record – it’s probably one of the least interesting songs on the record, but successfully suggests its broad themes and style. Following on from “All Souls”, though, is a sequencing gamble that threatens to swamp the mid-section of the album in sloth.

The gorgeous “I Inside the Old I Dying”, though, is one of the album’s gems with its shuffling percussion, Parish’s gossamer guitar part, and Harvey’s graceful melody; the uncertain vocal delivery was a purposeful choice – “I was standing in the vocal room with the headphones on, and Flood said ‘No, no–you sound like PJ Harvey.’” Harvey ended up recording the vocal with her eyes closed, unaware of where the microphone was, which lends it its blurred, out-of-focus quality. “Flood would just experiment all the time like that, to find the thing he wanted,” says Harvey.

The same can be said of the magnificent opener “Prayer at the Gate”, which is sung, as a lot of the album is, in Harvey’s upper register – but there is a warmth and strength in the delivery that is so much more appealing than on Let England Shake or Hope Six. It’s a beautiful, emotional invocation that recalls some of her work on the All About Eve soundtrack and, at its climax, Harvey sings in an unabashed, radiant high vibrato that is somewhat new for her and possesses a real yearning and sad desperation. It’s a beauty.

At the opposite end of the record, “A Noiseless Noise”, seemingly from nowhere, brings out a heavy, propulsive rhythm not heard on a Harvey record in a while and she also unleashes a vocal that is pure Stories grit, power, and sheen. As much as one respects Harvey’s resolve in not wanting to repeat herself, it’s a joy to hear something a bit more unbridled again that, to her credit, hangs together well with the rest of the material.

Although comparisons with earlier records might provide loose reference points, ultimately comparison is futile in trying to pin down the sound of an album that simply will not be pinned down – I Inside the Old Year Dying succeeds where all Harvey records do, in breaking new ground for her. Its plaintive beauty and major/minor contrasts recall some of her more intimate work and it exists within the same world as Harvey’s more apparently personal, “English” work, but there is a newness in the decision to include more found sounds and effects – birdsong, bells, schoolchildren, strange nocturnal noises – that make it sound alive, immediate, and particularly with Orlam as a base text, it’s definitely its own universe.

Somehow, though, it feels transitional. It doesn’t present as a bold step forward, nor Harvey’s most daring volte-face. This isn’t to say it is not an important artistic moment for Harvey – in many ways, it might be one of her most personally important records. Breaking new ground doesn’t need to mean something entirely leftfield. It feels like a gentle but decisive turn towards a new direction, the sound of Harvey making sense of where she is at artistically. It’s the sound of an artist who had obviously been uncertain where to go and how to go about it but has pulled the threads together into something meaningful for her creative future – Harvey speaks about being “broken-hearted” at fearing she had fallen out of love with music after 2017, and how she slowly found a way in again by playing her favourite songs by other artists on the piano or guitar – Nina Simone, The Stranglers, The Mamas and the Papas.

I Inside the Old Year Dying is probably most important because it represents Harvey’s vision clearing – the confusion about which direction to take, having become more comfortable with writing music as accompaniment to existing work and focusing on poetry, has crystallised into the realisation that there needn’t be a choice. At one point, Harvey thought I Inside the Old Year Dying might end up as a stage piece; instead, it’s its own world on record, the aural cousin of Orlam. Harvey describes it as a “resting space, a solace, a comfort.” That can be said for both its content and its result.

I Inside the Old Year Dying is a record that takes time to find its way in. There is more to uncover than might first appear – which is also one of the general themes of Orlam and the associated song lyrics. You’re never quite sure exactly where you are – Harvey’s voice is often mixed very much front and centre but is deliberately contrasted with the reverb in the instrumentation and the comparatively dry recording of the percussion to create an eccentric, ambiguous hinterland that moves in and out of focus.

“I’m somewhere I’ve not been before,” says Harvey. “What’s above, what’s below, what’s old, what’s new, what’s night, what’s day? It’s all the same really – and you can enter it and get lost. And that’s what I wanted to do with the record, with the songs, with the sound, with everything.” On this basis, Harvey has succeeded in her aims.

There is enough here that suggests both a looking back and a looking forwards – again, that bridge between new and old, the past and the future, the real and the fantastical. As ever, where she goes next is anyone’s guess.