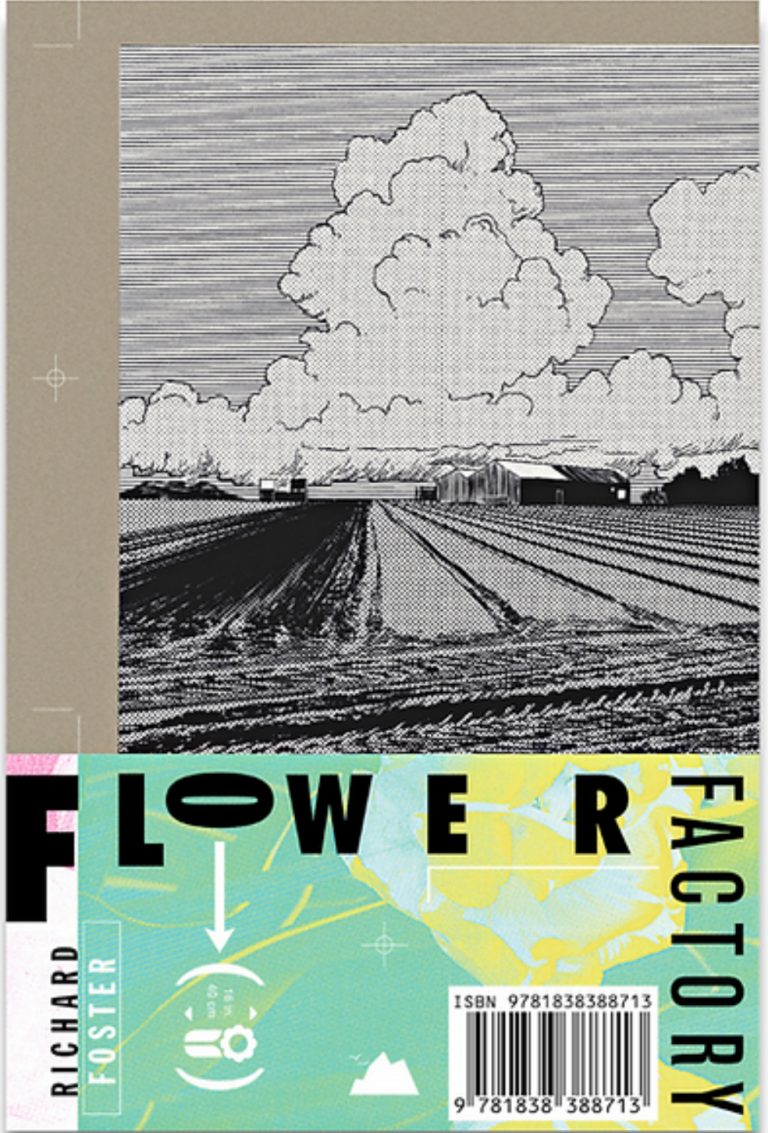

A man known more for his vigilant reportage of the European music scene than his fictional exploits, Richard Foster’s debut novel, Flower Factory: A Fairytale, threatens to change this, adding nuance and melancholy to the brazen prose of his journalistic work.

Set in the year 2000, Flower Factory tells of Foster’s first year as a casual worker newly emigrated from the UK to the Netherlands. A new millennium looms, and the Freedom of Movement concept is being fully explored on the continent. The author remains a nameless narrator in this roman à clef, bearing witness to the squat scene of punks and ravers drawn from across Europe by “the resonances of the Magic Centre of the Universe, Amsterdam”. Through a series of vignettes, soundtracked by a collision of inescapable mainstream radio and old-school punk and metal, Foster presents a world – and a man – on the cusp of change.

Foster’s prose is one of the main draws of the novel. It’s colourful and sophisticated, laden with both high and low brow references to keep the reader engaged in what is, essentially, a social history. Rather than spell out his political and philosophical views, Foster’s narrator remains present in the moment, recording and inviting analysis. This technique leads the reader to question the work, a brave decision perhaps born out of our ability to remember moments more clearly than thoughts.

One question in particular hangs over the novel, accompanying the narrator on every solitary bike ride, and lurking in each bout of “bulb finger”: Why put yourself through this? Foster, in the novel’s introduction, addresses his reasons for emigrating, citing a vague “feeling that nothing was panning out” in his home nation. Yet, emigrating is not portrayed as a quick fix, and as the protagonist sidles from factory floor to poky bar to pillowless caravan bed, a sense of oppression and claustrophobia seeps in.

One scene finds him tasked with collecting and packing an order of dreaded Hyacinth bulbs, the effects of their husks and discharge on the body described in visceral detail. In moments like these the omnipotent question appears centre stage, silent, unmoving. Still Foster refuses to acknowledge it; the narrator gets on with the job at hand.

Though it doesn’t provide untold riches or a perfect life, through his acceptance of such bitter occurrences the protagonist suggests that Freedom of Movement is still worthwhile. It provides him with a chance to start anew. And he is not alone. A cosmopolitan assortment of characters flash before Foster’s literary lens, veering in and out of focus, vivid and ephemeral.

Flower Factory is a portrait of the no longer existent. The term ‘Fairytale’ is apt not because this is a magical story, but because the realm it inhabits is a slightly altered version of our own reality, beyond – or more accurately, behind – our grasp. The novel is esoteric and slow-burning, nuanced in the way it encourages the reader to grapple with history. Despite the events of Flower Factory occurring well within living memory, it’s a period that feels to be fading rapidly from the public consciousness. In a post-Brexit UK, Foster’s novel recalls the privileges since lost.