The terrible thing about ageing isn’t just the steady decline of health and wits, but the realization that you are being left behind. Friends no longer call. Partners become distant. Children are more and more absent. Technology and the outside world become scary while the places you once considered as formative inspirations vanish. Media and art are no longer comprehensible, seemingly turning more extreme with each passing year.

Dialogue between elders and the young seems to have, for the most part, ceased, as it’s becoming clear that it’s impossible to find common ground. This division of generations has been chronicled as of late with the ‘Ok, Boomer’ meme, a humorous one-liner that attributes conservative and isolationist perspectives inherent to parental generations to a myriad of characters. You don’t have to be old to be a Boomer, but most are far removed from the realities of modern living. They become irrelevant, cranky and naïve, ignored and laughed at by their children and grandchildren.

Yet there are the rare examples of individuals from the Boomer generation that transcend the cliché, and become people with whom Zoomers and Millennials alike seem smitten to the core. Look no further than the adoration Bernie Sanders, David Lynch and David Bowie still receive. Still relevant – and still vocal (those living) – they fill the roles of societal elders, wise men who dare listen and learn at every turn, transforming the anxieties of younger generations into assurance, guiding and inspiring entire movements. It’s easy to be adored, just as it must be relatively safe to retire.

However, the hardest part must be to stand between those lines, simultaneously a memento of the past but also attempting to fit in alongside the cool kids. No musician of the past personifies this better than Paul McCartney. A giant of the art form, he’s outlived many musicians he originally inspired. But leading the world’s most significant cultural entity comes with a price. Over the years, he has been derided and mocked. Some of his best-selling tracks are widely considered some of the worst a Beatle has ever recorded, and young Paul famously wondered if he’d still be relevant at 64.

At the same time, McCartney has never shied from the obscure and bizarre. 1980’s McCartney II has been re-assessed as a triumph of new-wave weirdness, while his mostly obscure collaborations with Killing Joke’s Youth as The Fireman is often brave and surprising. McCartney has tried everything and, bizarrely, only fails whenever he tries to fit other people’s expectations. And so, at 78, stuck in lockdown, McCartney enters his seventh decade as a musician with a ‘spiritual follow up’ to a quirky, experimental album made 40 years ago, recorded all by himself and based on leftovers from over the decades.

The weight McCartney III bears seems inevitable: will this be some sort of salvage-job, an attempt to pass boredom? A tired re-tread of an album still considered controversial by many hardcore fans? or just a continuation of the slightly too typical precursor, Egypt Station, making the titular connection to the past a barren reference?

In the end, the album manages to evade all of those pitfalls. McCartney III dismisses the polish of his past few albums and sports a decisively ‘back to the roots’ sound that is practically brimming with joy. McCartney sounds younger here than on his last two projects, layering his vocals and letting his songs’ structures grow wild.

Opening couplet “Long Tailed Winter Bird” and “Find My Way” sport a slight hint of anarchism. With their energetic guitar playing, they’re on the verge of sounding like John Lennon compositions – “Lavatory Lil” could even be a direct reference to his “Polythene Pam”. This surprising likeness to his best friend’s aesthetics is nowhere more apparent than on the album’s centrepiece, the eight (!) minute long “Deep Deep Feeling”. Sort of a “What’s the new Mary Jane” sibling, the song drifts and morphs over its long runtime, finding a darkly psychedelic ambience, which in itself plays with space and clarity of sound. Those ideas might not be revolutionary, but they make the song incredibly engaging.

III’s biggest strength is that it never forces McCartney into something he isn’t inherently comfortable with. Everything here feels effortless and, for the most part, timeless. “Slidin’”, a blues-rock song in the Abbey Road vein, has shades of a Jack White aesthetic, while “Seize The Day” is a reminder of where Queen and 10cc took their punches from. The fine ballads “Pretty Boys” and “Women and Wives” allow McCartney to flex his usually solid grasp of observational lyricism, but it’s a shame that his voice sounds a little fragile on those tracks, leaving the romantic “The Kiss of Venus” as the strongest ballad here.

Still, III isn’t perfect. “Deep Down” is repetitive and, in its odd solemnity, like a tired Flowers in the Dirt outtake. Then there’s the closer “Winter Bird / When Winter Ends”, recorded by George Martin a few decades ago. It’s a clean, cute little performance, but it feels thoroughly anachronistic. The callback to the opener raises questions – is silver-haired McCartney seeing himself as some sort of winged critter, briskly fluffing its plumage, hopping about, facing the cold with grace and good spirits? It’s a little inconclusive, a little too harmless for an album mostly showing his keen ear for catchy melodies and inspired, sometimes even heavy guitar playing.

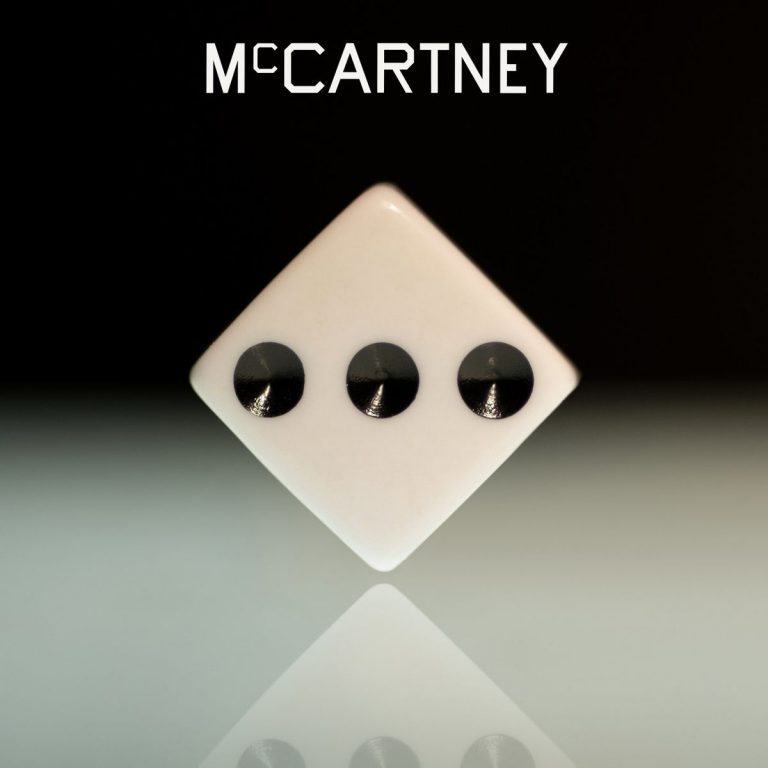

As a whole, McCartney III is lean, lightweight and unpretentious. Where so many of his collaborators of the past forced a sound aesthetic on him, here he is free to allow the studio ambience and guitar tones to carry youthful quirks. The gloomy sobriety of the cover’s artwork is actually misleading. It’s clear that McCartney isn’t too low at his age. Instead of ruminating on his mortality, he’s dancing on TikTok and delivering what is one of his most likable rock albums of his career – an album that doesn’t feel like it requires jokes, or Mark Ronson, or big orchestral pomp to hit the mark. Even if it isn’t the notable stylistic statement that McCartney II was, it still feels poignant, and yes: surprisingly youthful.