I’ll admit that I didn’t think I’d have the chance to review a new David Bowie album, but here we are, ten years after Reality and with little forewarning. It’s difficult to consider new releases by legacy artists like Mr. Bowie–artists who have nothing left to prove, who have already cemented their legacy and, common wisdom assumes, whose best work is behind them–on their own terms, and many of the reviews I’ve seen for The Next Day spend as much time discussing Bowie ‘The Reclusive Artist’ as they do discussing, you know, the album. They mention that Bowie’s largely been silent for the past couple years; they note that it turns out he’s been working on this album with longtime collaborator Tony Visconti (Space Oddity, Young Americans, Low). They are calling this Bowie’s latest big comeback.

I contend the opposite: this is not a comeback album. That implies a rejuvenated career, a “second wind,” if you will. But there have been no plans for a tour to support this album, no talk-show interviews, no press releases announcing renewed label contracts. More importantly, Bowie doesn’t sound like he’s making a comeback here. On the chorus for the title track opener, he proclaims his return in not-so-grand terms: “Here I am, not quite dying, my body left to rot in a hollow tree.” A slightly off-kilter guitar buzzes in the background and it’s like we’re back in 1973, only Bowie’s far more paranoid than he was even when instructing fellow party-goers to “watch that man” who “talks like a jerk but he could eat you with a fork and spoon.”

Indeed, this is Bowie’s darkest, most morbid work in a long time, at least from a lyrical perspective. Second single and third track, “The Stars (Are Out Tonight),” is hardly a wide-eyed gaze at the cosmos: “They watch us from behind their shades,” he tells us, “Gleaming like blackened sunshine.” Next song “Love is Lost” is no less dour, though it’s addressed to a twenty-two-year-old. “Your house and even your eyes are new. Your maid is new and your accent too,” he concedes. “But your fear is as old as the world.”

What’s unusual is how much Bowie’s sullen musings on death, mortality, cynicism, and faded glory clash with the music itself. “The Stars” is a buoyant pop rock number, complete with shaker, hand claps, and a romantic string section; “Love is Lost,” meanwhile, allows a psychedelic organ drone to take a bit of the edge off the crunching, submerged guitar riffs and the raucous, shouted backing vocals that punctuate the chorus like a group of inebriated barflies starting one more singalong to the old dusty jukebox in the back corner. Even the opening track, the one on which he lets us know that “First they give you everything that you want / Then they take back everything that you have,” sounds more upbeat and, well, rocking than its lyrics would let on.

The first single “Where Are We Now?” probably sounds the most like it feels. In it, Bowie’s characters wander across bridges and department stores, “just walking the dead.” Strings and piano contribute to the melancholia, though the searing guitar work keeps the song from getting too bogged down in its own pathos. It’s a beautiful number, like Ziggy Stardust risen once more to look back and offer regret. But even here, within this relatively straightforward sadness, there’s a troubling ambiguity that belies the instruments’ sentimentalism. “As long as there’s me / As long as there’s you,” Bowie trails off at the end. Is this a hopeful exception to the zombified shuffles of the characters we met earlier? As long as there’s me and you, I know where we are and that we are alive. But he sounds so damn sad singing it. Can you address a funeral dirge to someone still living?

The pounding “If You Can See Me” features an urgent cymbal-heavy rhythm and news-bulletin keys. On it, Bowie furthers the paranoia, speaking of his “fear of rear windows and swinging doors.” This time, however, there’s an aggressive edge; he has “a love of violence,” which goes nicely with his commandment to “take this knife and meet me across the river.” This song also sounds like it feels, but I’m more focused on the titular phrase: “If you can see me,” Bowie says, “I can see you.” The key word in this lyric is probably the first; if we can see Bowie, then he can see us. But what if we can’t see him? What if we think we’re seeing him but actually are seeing the vision of Bowie we’ve built up in our minds? Would it matter? Bowie almost boastfully contends that it probably doesn’t: “I could wear your new blue shoes. / I should wear your old red dress / And walk to the crossroads.”

The act of seeing is important to The Next Day. In fact, it’s probably the album’s most paramount theme, above death or the past or even that ever-present paranoia. (And what is paranoia anyway but a fear of being watched?) On “Boss Of Me,” a spry midtempo number punctuated by jazzy horns and a rollicking bassline, what begins as a sweet if nostalgic romantic number before long develops something of an existential crisis: “You look at me and you weep / For the free blue sky.” And on “Dancing Out In Space,” a cosmic and appropriately danceable jam, Bowie says that “No one here can see you, dancing face to face.” Bowie later compares this dancing to drowning, though the music of course grows no sadder with the revelation. Throughout the album, Bowie notices a lot of things; he “can see the magazines” and can even see what no one else can: “You moving through the dark.”

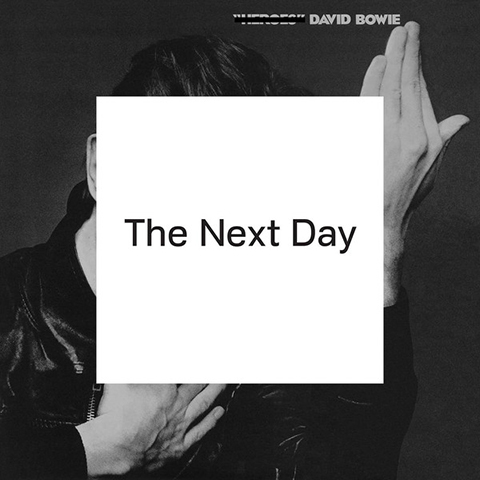

When we look at something, what do we really see? Do we simply see what’s in front of us, or do we see an amalgamation of all its past forms? Can we ever just see what we’re looking at without our vision being clouded by experience and judgment? Could we ever hear The Next Day without hearing all the Bowie we’ve listened to before, or is it destined to be “the latest in the artist’s storied discography,” a not-Aladdin Sane or not-“Heroes”? I think Bowie knows the answer to that question, and he knows we know the answer too. Thus the album cover: here’s his new work, but we’ll only hear traces of his earlier stuff in it. It’s an admission that we can no longer see David Bowie the person without also gazing at Bowie the legend, Bowie the institution, Bowie the big star (“You’ve got my name and number”), Bowie the soundtrack to so many of our memories. It must grow tiring to have to underscore your own humble humanity in the face of such admiration; for all his achievements, Bowie on this album is still just as scared, worried, and hopeless as the rest of us can be. I wonder if you ever get used to it.

He doesn’t sound 66 on this album. He doesn’t not sound 66 either, but another striking feature of The Next Day is how much it doesn’t sound like an old man trying to keep up with the times. There’s a confidence exhibited here that’s refreshing, from the adroit melodic moves of the singles to the “ya ya ya” chanting on “How Does The Grass” and the very 70s-classic-rock-sounding chorus of the infectious “(You Will) Set The World On Fire.” Bowie speaks with aged wisdom, but he’s not coming back. Maybe he never left in the first place, or maybe he did leave but hasn’t actually come back at all. One can imagine a throng of admirers, shouting for his autograph and asking whether it feels good to be back in the spotlight. “Is it I who’s in the spotlight?” Bowie might ask. “Or is it the David Bowie you’ve lived with for forty some-odd years now?”

“Is this your comeback?” the crowd asks next. Bowie smiles knowingly but says nothing for a moment. “That depends.” He pauses, looking out at the screaming fans thrusting pens and posters and album covers and unbridled, starstruck hopes in his general direction. “Do you see me?”