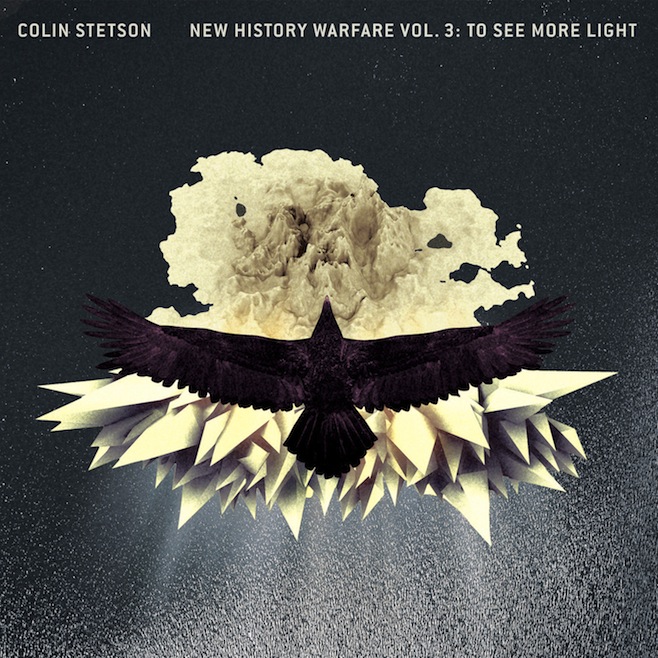

Bass saxophonist Colin Stetson’s latest release New History Warfare Vol 3: To See More Light is bound to be as thoroughly dissected and analyzed as any of his previous records. There is something inherently technical—though still relatable—about his music, and this can lead to critics emphasizing the precision over the emotion—the method over Stetson’s apparent musical fervor. And while all these critiques are valid, if slightly monochromatic in their evaluation, to fully appreciate the wonders and ridiculously complicated rhythms of his music, there must be an equal presentation and appraisal of all aspects of the music. It’s no coincidence then that his last few solo records, barring the Those That Run EP, have all been labeled as consecutive volumes, as he has been in a continual cycle of reinvention and refinement, with each release expanding and improving on the ideas that he toyed with on previous albums.

Theses could be written (hyperbole of course, but just barely) describing the method of recording and execution that Stetson has employed on his recent releases. The difficult to master circular breathing technique that plays an integral part of his compositions, as well as the tangible aspects of playing a saxophone so large that it must be strapped to his body, all demand an emotional and physical pledge that few artists are willing to make. But even removing the impressive physicality of his performance, what really comes across is the range of emotion and degree of exacting sentiment that he is able to extract from the sounds of clacking keys, the whoosh of air through multi-directional valves, and the sometimes arrhythmic notes of the saxophone itself. With dozens of tiny microphones covering the exterior and interior of his instrument, Stetson is able to receive both tonal and atonal input from numerous points and translate those signals into something fascinating and ultimately relevant to the conversation regarding modern music.

But all this talk of relevancy and of adding to a collective discussion of music—while appropriate—would be moot if the songs didn’t resonate emotionally with the listener. And with additional help from fellow musician and frequent collaborator Justin Vernon (whose vocals are the only overdubbed aspect of the music), the songs on To See More Light are as devastatingly personal as they are emphatically otherworldly—inhuman sounding even. This stark dichotomy of sound and intent throws Stetson’s music into austere relief. How can we be expected to invest ourselves in music when it seems to purposefully go out of its ways to sound like nothing that we’ve ever heard before? And conversely, how can something so superficially dissonant be so engaging? This curious sensation of distance and intimacy is what has allowed Stetson’s work to be so collectively loved and thoroughly debated.

The brief opening track “And In Truth” goes far in establishing the extremities to which Stetson and his work find themselves bumping up against. Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon lends his muted croon to the swirls of pinging saxophone notes and the resulting tonal clarity can take your breath away. But first and foremost, Stetson is an experimentalist, and we are never as safe as we think we are in his company. The inhuman wails and precisely plotted cacophony of man and instrument press right up against the speakers on follow-up “Hunted.” And it’s here that we get our first true glimpse of the way in which he blends the dissonant squalls of the notes, the moan of breath being drawn through rapidly opening and closing valves, and a melody that shouldn’t be able to survive in this ever thickening musical gloom. But regardless of how alien the sounds and tones become across these 11 songs, we’re never left to wonder about the human element behind this seemingly disparate series of rhythms and cadences. He’s there. It just seems that he prefers you to pay more attention to the music that you do to him.

Much like Tim Hecker or William Basinski, Stetson revels in the feel and sound of tonal repetition and repeated musical phrasings. On “High Above A Grey Green Sea” he blends the whir of wailing vocals with cyclical runs of quivering sax notes and comes across sounding like the last spirit haunting some lonely Irish castle. You can practically hear the wind rising from the nearby cliffs, threatening to drown out his voice once and for all. Subtle jagged industrial touches add an extra layer of foreboding to an already bleak and desolate track and further bathe this song in a dim and hazy wash of desperation. Another shorter and subdued interstitial track, “In Mirrors,” seems ripped straight from The Wicker Man (1970’s, mind you) soundtrack and leads directly into the sturm und drang of “Brute,” where we see Stetson toying with as close to a cohesive melody as we’ve heard up to this point — though it’s difficult to call this song more accessible as Vernon’s vocals here seem to verge on metal territory. But even where the footing isn’t sure and there’s an almost tangible sense of imbalance, Stetson never loses sight of his goals, namely to siphon off as much life from his instrument as humanly possible.

Tracks like “Among the Sef” and “Who the Waves are Roaring For” seem to exist in some alternate timeline where Tom Waits wound up recording with composer Arnold Schoenberg and where he more than likely made numerous musical drunk dials to Miles Davis. And you have to know that at some point in the studio, probably mid-take, Waits started throwing live chickens across the room — just because he happened to have them on hand. Though Justin Vernon’s shifting vocal overdubs on “Who the Waves are Roaring For” seem to be channeled in from another universe entirely. The album’s back half seems to rest upon the title track “To See More Light” and its dense layers of amorphous notes and near impenetrable use of rhythmic repetition. The only closest analog would be to some of the longer, drone-heavy tracks from The Knife’s recent revelation Shaking the Habitual. The album closes with “Part of Me Apart From You” and he seems to borrow piecemeal from the previous tracks. It seems to be a purposeful amalgamation of all the ideas that Stetson has been so slavishly devoting himself to for the past 50 minutes.

Colin Stetson is a saxophonist. And I imagine that is how he would want to be remembered, should he ever grow tired of his day job of obliterating and then meticulously reconstructing our senses. But for now, we have New History Warfare Vol 3: To See More Light and, of course, his past excursions into his own musical psyche to help us see that there can be darkness with light and intimacy with indifference. He’s just left it up to us to figure out which is which.