Man, Clarence Clemons, you picked a hell of a summer to die. This was the year, Big Man. After years of derision and snark — I blame that jerk, Kenny G — the sax was back! Now I’m not necessarily accusing you here; I can barely stand the Boss, but you shred on “Jungleland.” But, ever since Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street,” came out in 1978, the sax solo has more or less epitomized the worst parts of rock and roll; the schmaltzy, soulless camp that could only be cooked up by a bunch of white dudes in suits who dig Bob Seger.

Granted, the sax has been a part of rock n roll more or less since its inception, with Joey Ambrose manning the horn for Bill Hayley’s Comets helping to bridge the gap between blues, jazz, rockabilly, and country that would spawn rock. It fit, it worked, and plenty of horn sections would pop up throughout the ensuing decade, especially as artists like Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart started dabbling in avant-garde rock and jazz fusion (and anything else they felt like including). But with prog-rock slowly nearing its tipping point of excess and absurdity, it’s no surprise we get something like “Baker Street” in 1978, which for all intents and purposes is patient zero of the new era of sax solo. The ensuing decade was a mélange of hot-air-blowing musicians trying to tap into rock’s roots by slapping a pair of Ray-Bans on some mustachioed jabroni and having him wail on the sax for a few bars, the producer probably screaming, “More blaring squeaks!” or “Smoooooother!” Now there’s certainly some decent stuff out there, like “Dancing In Dark,” Rick James’ “Super Freak,” Duran Duran’s “Rio,” obviously Hall & Oates’ “Maneater,” and I’ll always have a soft spot for Huey Lewis & The News’ “Back In Time” (Back To The Future is the best movie ever). But crap like “Baker Street” or Foreigner’s “Urgent” has forever tainted the good songs. Yet here we are in the summer of 2011, and it’s like four months of monster songs with kick ass sax solos.

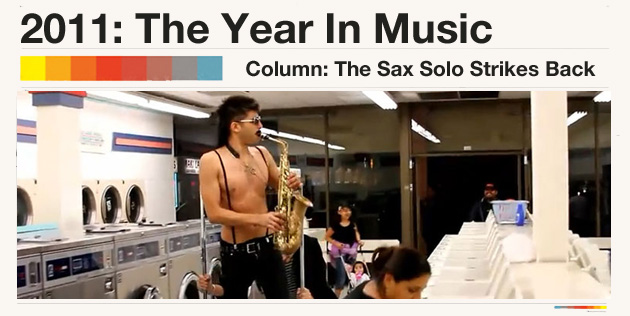

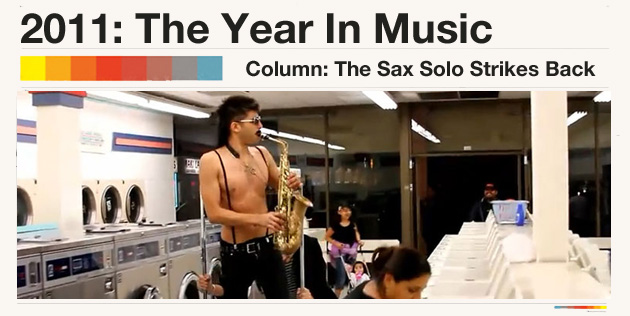

Technically, Summer Of The Sax Solo ‘011 kicked off with Destroyer’s excellent Kaputt, a meticulously constructed record that made soft rock sound impossibly cool; almost every song was accented with trumpet or sax flourishes that snapped me back to sixth grade when every morning I’d get on the bus and Mort, the driver, without fail had the radio dial turned to WJJZ 106.1: Philadelphia’s Smooth Jazz Station. But it wasn’t until May when I was poring over reviews of Lady Gaga’s Born This Way that of course mentioned then-single “Edge of Glory,” which was climbing the Billboard charts and featured a solo from Mr. Clemons himself, that things started coming together. The whole point of Born This Way seemed to be about tapping into coke-fueled 80s excess, so Clemons’ spots on “Edge of Glory” and “Hair” seemed appropriate enough, and made the tracks all the better. Then about a month later I was watching the 8-minute music video/short film for Katy Perry’s “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.),” which was chock-full of jean jackets, glaring neon, clichéd high-school hierarchies, and then freaking Kenny G himself is standing on top of a roof busting out a fat sax solo, and not only was it hilarious but it kinda, sorta really rocked. Then, as if it to solidify Summer Of The Sax Solo ‘11, The Rapture and M83 dropped superb singles, “How Deep Is Your Love?” and “Midnight City” respectively, that both ended with fade-to-black saxophones. Oh, and not to mention Bon Iver’s horn-saturated self-titled record that debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200.

It’s no surprise that all this happened this year. With 2011 marking the un-officially official 20th anniversary of grunge, musical and cultural nostalgia shifted its focus firmly onto the 90s with plenty of box sets and reunion tours and documentaries and Nickelodeon re-runs. It’s as if everything from the 80s that seemed worth remembering had gotten its due over the course of the aughts, but that didn’t retroactively negate the existence — or underlying influence — of sillier genres like jazz- and/or soft- and/or yacht- and/or dad-rock. That’s not to say Dan Bejar or Justin Vernon – or Dr. Luke for that matter – (re)turned to this style solely because there was nothing else left, because implicit in all this new music is an undeniable appreciation of the original and a certainty that this horn sound can be wielded in a way that doesn’t elicit groans. It’s very obviously pastiche, not satire — and very well received pastiche to boot. Both “Edge of Glory” and “Last Friday Night” were massive hits, while “How Deep Is Your Love?” and “Midnight City” showed up on plenty of critics’ year end lists, as did Bon Iver, Bon Iver and Kaputt.

On the surface though, it’s a bit odd that praise for Dan Bejar comes in the form of a comparison to Chuck Mangione, or Justin Vernon to Bruce Hornsby, musicians mocked for making adult contemporary schlock filled with emotional platitudes. In its initial form, all that stuff, especially the sax solo, was pure camp, completely earnest in its devotion to an over-produced aesthetic, yet naïve to its absolute forehead-slapping goofiness. But thanks to 25+ years of distance and post-ironic appreciation, the saxophone in the middle of “Last Friday Night” or at the end of “Midnight City” is immediately arresting. It confronts the listener with a sound that pop history dictates should sound cheesy, but in this context it doesn’t, it almost sounds pure, natural. It grounds the songs in a sort of reality standing in stark contrast to computerized, synth-pop bases or even the crunch or twang of a guitar that’s been sent from the strings to the pickups to the chord to the amp before finally reaching the listener. It glides in with this kind of grace to the point where you can hear the exhale itself behind this honk, this delicate honk (and that catches you off guard because, delicate honk!?) that you realize is so malleable. It can wail, it can sail, screech, bleat, roll, rumble, climb to these ridiculous heights, a gust of wind that can just take the weight of an entire song and carry it on its back. It makes these songs that much better.

Nostalgia’s definitely at play here, but it’s a peculiar kind of nostalgia. I don’t doubt that these songwriters enjoy this style of music and saw in it possibilities that others had missed or ignored due to the, well, major un-cool factor. In that sense, it took some cajones to basically go, “screw it, we’re going all out on this one,” and be confident that it was the right decision. (Admittedly, Bon Iver caught some flack for making what many saw as a snooze-fest of a record, but many praised Vernon’s desire to tap into that sound.) But on the side of the listener — and perhaps this is somewhat of a gross generalization — you get the sense that many people didn’t know they were nostalgic for this sound until it was staring them right in the face. I sure didn’t. But then maybe it’s not nostalgia I’m feeling. I mean I wasn’t even alive to shit on (but secretly appreciate) the music of Bruce Hornsby or Lionel Richie in the first place.

The fear over nostalgia that’s popped up over the past year seems rooted in the notion that our obsession with the past hinders our ability to look forward, to create something totally new and unique solely to this generation. English music critic Simon Reynolds calls this “hyper-stasis,” and he argues that we’re currently stuck copying and pasting elements of different genre, creating something that only appears new. It’s bleak, yeah; but what if that’s all we can really do at this point?

“There is another sense in which the writers and artists of the present day will no longer be able to invent new styles and worlds — they’ve already been invented; only a limited number of combinations are possible; the most unique ones have been thought of already,” said Frederic Jameson in a lecture called “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” given in 1982. Again: Bleak. But then again, over the next twenty years we got, to name a few, hair metal, twee, post-punk, techno, grunge, new wave, and, yeah, smooth rock — all of which pilfered from the past, yet existed as unique, individual genres. Re-contextualization has helped create some some fantastic moments throughout pop music’s evolution, and will continue to do so — perhaps next year’s sax solo is the fret tapped guitar solo, which a small crop of bands (like personal favorites Diarrhea Planet) have started busting out for the first time since like the heyday of Yngwie Malmsteen because, yeesh, who wants to be tangentially associated with Yngwie Malmsteen? Well, some people! And thank god, because our musical past still has plenty to offer us in things that we’ve maybe discarded or prematurely deemed unworthy, and letting these sounds or styles drift into oblivion rather than experimenting with them in new ways would be a waste. The problem with Reynolds’ hyper-stasis concept is that its view of novelty is too narrow, ostensibly refusing to acknowledge the uniqueness and freshness of a song that, say, combined pop with dance punk with 80s adult contemporary. Because the first time I heard “How Deep Is Your Love?” I sure as hell couldn’t think of anything quite like it.